The Lancastrian Women Transported to Australia

Elizabeth Youngson- The Child Convict

Elizabeth Youngson- The Child Convict

Elizabeth is the final Lancastrian woman in this series,, though in fact she was not a grown woman at all, but a 13 year old girl when convicted. Somewhat of a record breaker, she was not only the youngest Lancastrian female convict but the first; arriving as part of the First Fleet in January 1788 with her younger brother George who she had been convicted alongside of.

.

Elizabeth and younger brother George had been discovered breaking into a Moor Lane silk warehouse belonging to James Noble in the early hours of 15 September 1786, they had stolen 41 shillings. It’s possible this was also their workplace as money had been going missing from the office for some time. Held at Lancaster Castle until the Lent Assizes the following year, they were found guilty and sentenced to hang, though were reprieved and were to be sent to parts beyond the sea for 7 years to help form a new colony in New South Wales. They joined a mixed group of men and women who were also awaiting a similar fate in the castle’s cells.

.

Within weeks of conviction, the siblings were whisked to Portsmouth where they were put aboard the Prince of Wales convict transport ship which was due for departure. This would then travel in convoy with five other convict ships, a supply ship and a flagship to Botany Bay to establish the colony. George was the only male convict onboard. After a long nine months voyage which was plagued by lack of provisions and terrible living conditions. Elizabeth and George arrived at Sydney in January 1788.

Elizabeth, now aged 16 or 17 and her brother were shipped to Norfolk Island the following year where a new prison colony was to be formed. During the years she spent on Norfolk Island Elizabeth had three children. She returned with her brother and a daughter to Sydney in 1794 and sadly no further records can be found for George after 1794. Elizabeth married fellow convict Abraham Lee in 1798 whilst she was aged around 26 though they may have separated as she had another daughter, Anne to a different convict in 1808 whilst Lee was still alive. By 1819 Lee had died and she was now listed as a widow. By 1822 though she is listed as living at Parramatta with Anne and was said to be wife of another convict, James Hathaway whom she had married two years prior and been living with for some years. By 1825 she seemed to be alone again.

She was described in a 1836 gaol record as 4ft 10, slender, pale with brown hair and grey eyes, a Protestant and born in 1773. She lived a very long life for the time, dying July 1854, aged 82.

Image: ‘Le frère donne les étrennes à sa soeur’, L.M.Bonnet c.1746–1793 courtesy of the Clark Museum

Mary Grimes- The Innocent Convict

Mary’s case is a fascinating one; wrongly convicted and sentenced to transportation and finally freed after a mysterious letter and the local newspapers helped clear her and her father and friend of assault and highway robbery.

27-year old Mary, her father John and his friend Paul Rigby, all pedlars, had been on the road on Shrove Tuesday, February 1830. They had come from Garstang through Galgate and been drinking at the Boot & Shoe and Mary had begged a passing traveller for a ha’penny without luck at Scotforth. Several hours later at a Lancaster lodging house, they were suddenly arrested, charged with a brutal assault and highway robbery on the passing traveller, a Robert Stanley of Oswestry. Stanley had been beaten and had been tied with wire by the neck and hands to a gate at Bellevue, he was almost suffocated when he was found and aided by locals that evening. A large public collection was made for the man.

Mary and the two men were held until the next assizes at the castle. Evidence given by Stanley led to a death sentence for John and Paul and transportation for life for Mary despite their protests of innocence. Robert Stanley hurriedly left Lancaster (oddly for Liverpool). In the following days, doubt crept in, thanks in part to the local network of newspapers. Local residents of Oswestry, reading about the case, quickly wrote to say ‘there was no such person as Robert Stanley in their town’, nor was there a Rev. Thomas Venables who had written a character reference for Stanley. A respite was ordered on the executions while enquiries were made.

In the following week, Wolverhampton police came to Lancaster. They had had an almost identical ‘highway robbery’ the previous year, again a man called Robert Fisher had been found beaten, robbed and tied with wire to a toll gate on the edge of town. On the 19th March an anonymous, badly written letter was received at Lancaster Castle. In it the writer confessed it was them and a partner that had beaten and attacked the man at Galgate and the other three were innocent. The writer said they needed money and had committed a number of these attacks so they could move to find work and were now in Ireland. Robert Fisher and Robert Stanley were clearly one and the same and a skilled actor to play the injured party too. A spate of copy-cat ‘attacks’ took off around the country for several years following.

With enough evidence, and having served over two months in jail, Mary, John and Paul were freed, receiving a full pardon in May, the victims of a huge miscarriage of justice.

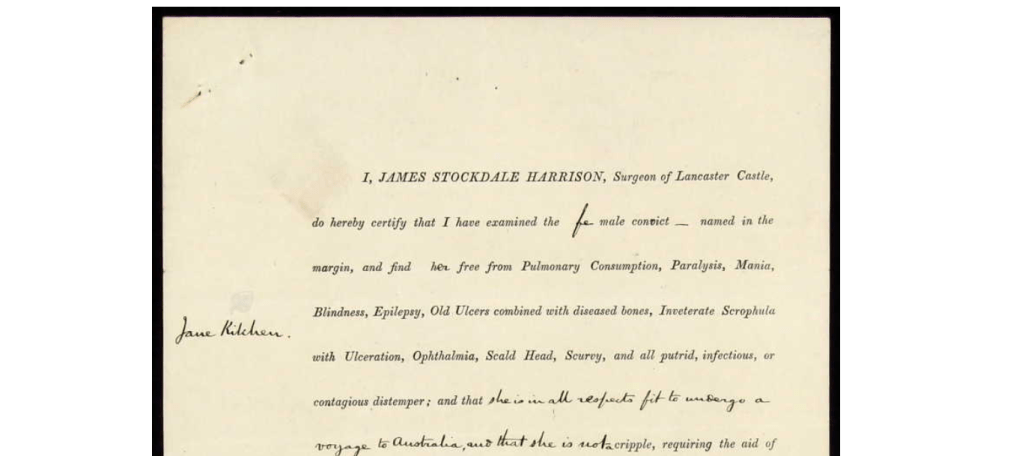

Jane Kitchen- The Bonnet Thief off the Hook

As we have previously covered, not all the women who received a sentence of transportation actually ended up in Australia. Some, like Jane Kitchen through unusual circumstances, escaped. A number of documents, some of her own telling, provide a surprisingly personal look into her life…

Jane was born and baptised at Halton in 1819. As a child she attended the Ladies Charity School in Lancaster for six years before taking up employment as a housemaid; first at the house of Rev William Fenton in Bleasdale until his death. Then at John Bowers’ in Bare for two years before moving to John Thompson’s house in Lancaster before ill health forced her to leave. She then appears to move to Preston and this is where she commits the first of two crimes leading her to short term prison sentences in Preston’s House of Correction. Acting as a servant she pretends her ‘mistress’ has ordered a bonnet to be sent to an address to be collected; in other words obtaining goods through deception. It’s around this time, in 1841 she appears on the first census in Back Willow Street (one of the areas with the direst living conditions in Preston). She was living with three other young women aged between 20 and 25 all of ‘independent means’, mostly likely a euphemism for prostitution.

The following year in May, back in Lancaster, Jane ‘unlawfully obtained from Robert Allwood, two bonnets, his property value £1 1s’. Allwood was a linen draper at 5 Penny Street. Once again she had used the same strategy of pretending that she was collecting the order for her employer who would settle the bill. She was arrested and sent to Lancaster Castle where she went on trial at the 1842 Midsummer Quarter Sessions. Found guilty and with a track record of two similar crimes and a gaol report saying she was a ‘bad character’, Jane was sentenced to be transported for seven years.

While in jail at Lancaster, she wrote and signed her own petition, pleading for a reduction in sentence and to stay at Lancaster. In it she sets out her childhood and nine years previous work experience for respectable families before being forced out by ill health. Governor Higgin denies this petition going forward. Before leaving the jail for Woolwich and the transport ships, surgeon James Stockdale Harrison certifies she was free of all diseases and notifiable conditions and on 28 November she was sent south. Before being boarded on the convict ship Margaret, surgeon Benjamin McAvoy rejected Jane as not suitable to travel due to having a recently opened fistula. She was sent back to Lancaster. The magistrates back at Lancaster were far from happy about Jane being sent back with no paperwork and having been deemed fit to travel when she left. The Lancaster surgeon stated that she had previously been operated on at Liverpool and whilst her previous ailment had healed, the journey must have reopened it. She was operated on again and once healed would be fit to send back to Woolwich for transportation.

Still in jail in January 1843, Jane again writes a petition, pleading that she not be transported and be kept either at Millbank Penitentiary in London or at Lancaster, also asking that the eight months she had so far served be counted towards her sentence. Her request appears to have been granted with the governor saying make preparations for her transfer to the penitentiary. However, the surgeon doubts the medical officer will accept this due to her recent health issues. It is not then clear whether she was transferred or remained at Lancaster but what is known is that by August 1849 she was free and was getting married to a widowed 62 year old leather currier Henry Almond at the priory church; they appeared to be living together, both listing their address as Penny Street. Her unique signature on the wedding register and her jail petition match. The couple then move through to Preston where they live out their lives, having, and losing a number of children. By 1871 Jane was widowed and working as a confectioner, herself passing away in 1881.

Ann Simpson- The Bad Neighbour

One evening in spring 1835, 51 year Ann shared a celebratory drink with a neighbour, an Esther Battersby, who was telling her how she had just returned from collecting an inheritance. Seizing the opportunity, early the next morning whilst her neighbour was still waking up, Ann talked her way up into Esther’s bedroom in Wood Yard off lower Church St and whilst Esther was still confused and drowsy, used the ruse of distracting her by trying to get her to buy a bag whilst she stole a purse containing the inheritance money from under the bolster before heading off. Once fully awake and realising what had happened, Esther and her teenage daughter raised the alarm and Ann was apprehended near Lune Villa in Skerton, before being arrested on the Green Ayre and taken to the town hall. The purse was found on her and whilst the coins were there, the higher value notes were missing. Ann admitted her guilt but said she had no idea where the notes were.

Ann was tried as the Borough Police sessions in the town hall (now the City Museum) on the 9th April that year and was one of only two women to be given a sentence of transportation from the local police court (Mary Cawson who I’ve previously written about being the other). Like Mary, she also received a life sentence and was transferred up to the castle to await her fate. A failed attempt to petition the king meant that in September that year, Ann was put onboard the Henry Wellesley at Woolwich and sailed to Sydney, arriving in February 1836.

Whilst aboard the Henry Wellesley, Ann may have been surprised to see three Black women; named as Sue, Matty Beck and Peggy who had been convicted at Bermuda, Barbados and Dominica courts respectively. Slavery had officially ended the year before in the British West Indies though the colonisers were still keen to exert their control by transporting those now termed ‘apprentices’ to Australia.

Ann was described as 5ft 4 with grey hair, hazel grey eyes with a ruddy complexion and gave her occupation as a plain cook. She was a native of Cumberland and was married to John and had had nine children.

Having settled at Goulburn, 120 miles from Sydney in 1838, Ann received permission to marry a much younger fellow convict but before the wedding could take place it was discovered Ann had produced letters fraudulently claiming she was now a widow. At the age of 56 in 1841, Ann received permission to marry a 62 year old convict, Richard Nolgrove but this does not appear to have happened. Finally, the following year she married John Stone. Her ticket of leave was granted in 1844. Ann passed away in 1853 aged 68.

Margaret Mason- The Green Ayre Highway Robber

Aged around 30 with an alias of Moore, Margaret was charged with having on 21/12/1802 assaulted Bulk farmer Richard Harling on the king’s highway at Lancaster on the Green Ayre (therefore the turnpike now Caton Road) taking from his person £2 and 6 shillings.

Most highway robberies were like this; an opportunistic mugging, not the much romanticised horseback ‘stand and deliver’ type. The end result was the same though and Margaret received a death sentence, later reprieved at the March 1803 Assizes at the castle and was sentenced to life transportation. She was put onboard ‘Experiment’ (a mixed ship) which sailed for New South Wales in October 1803, arriving in June 1804.

The lack of documentary evidence after arrival suggests a quiet life. By 1828 Margaret was a housekeeper for Joseph Barnes at Parramatta who was probably her husband and by this time she was long free by servitude; somehow her life sentence had become a 7 year one, possibly due to an administrative error.

Margaret’s husband Joseph was tragically killed in 1843 when his cart load of manure fell on him, crushing him and after she carried on alone though in 1855, Margaret was a victim of her own earlier crime when she suffered a nighttime highway robbery at Parramatta. She described the two men in great detail, they took £1 5 shillings from her.

Margaret died and was buried at St Johns, Parramatta aged 85 or 89 (records vary) in april 1858, sadly having died a pauper at the benevolent asylum.

Mary Denton & Maria Davis- As Thick as Thieves

Together, Mary and Maria, both aged 25, tried to cash a stolen bill of exchange worth £9/11s in March 1800. They were tried together at the Lancaster Assizes, receiving equal 7 year sentences and were by each other’s sides during their first years in Australia.

After 7 months in Lancaster Castle’s dungeon tower, Maria and Mary were furnished with clothing and transported to Gravesend with 11 other women, and put aboard the Earl Cornwallis, a ship carrying both male and female prisoners. It arrived in New South Wales in June 1801 after a sickly journey where many convicts had died of dysentery.

Only 3 months after arrival, Mary married fellow convict William Howarth at St Johns Parramatta and just 3 weeks later; the next wedding registered at the same church, Maria married convict Samuel Haslam. The two women were witnesses at each others’ weddings though neither could write and both signed their mark with an ‘x’.

Maria went on to have 4 children. She helped her husband run a successful roadside inn on the road to Parramatta and the area around it became known as Haslam’s Creek. She received her certificate of freedom in Feb 1811. Living on a frontier road in a dangerous area in 1822, records show she was assaulted by a district constable in her own home (he was sacked after a trial), whilst as ‘an antiquated lady’ in 1826 she was woken and threatened with beheading by a gang who broke into and burgled her home; alcohol however seemingly clouded her memory of the event and she was unable to pick out the prisoner in a police line up. I have not been able to find any further records for her as yet.

After marriage, Mary had no children but did take in husband William’s orphaned nephew in 1809. She got her certificate of freedom in July 1810. In 1811, William died abruptly and Mary was receiver of all his estate. The following year in 1812 she then married Lancastrian convict Francis Battie/ Beattie and lived at Newcastle. In 1822 she is described as a convict in government employment (presumably after being convicted of a further offence) but in 1828 her and Francis are described as sheriff’s bailiffs- she has a horse and 30 cows. Mary died in 1836 aged 62.

Elizabeth Hodgson- The Repentant Convict

30 year old Elizabeth Hodgson, was convicted of stealing flannel from the shop of town clerk, Robert Lawson on Pudding Lane (now Cheapside) one evening in late February 1810. She had used that common trick of sending in a decoy who bought a small article, distracting the shop owner whilst she hid a large piece of flannel in her apron. Unfortunately for her, she was observed doing so by a neighbour and after running, was caught and apprehended.

Three weeks later, she was found guilty at the Lancaster Assizes and sentenced to seven years transportation. Fifteen of her friends, family and neighbours had a formal petition made to try and get Elizabeth’s sentence reduced to imprisonment. They stated how she fully accepted her crimes, having never been in trouble before and had been ‘dominated by a monster’ called Gideon Yates, who notably, was tried immediately after her at the assizes but was acquitted of stealing a coat on the same evening as Elizabeth’s theft. It went on to say she had been married nine years earlier to a sailor called Sulivan McCartney but as he had never returned from sea, she had resumed her maiden name. The petitioners stated that they never imagined that she would have been sentenced to transportation, only a prison sentence and more would have spoken up for her in court, had they realised what was going to happen. They refer to her as a ‘poor thing’.

Petition unsuccessful, Elizabeth had a long wait of over a year in Lancaster Castle before she was taken to the south coast and put onboard the convict ship Friends and was off to a new life in New South Wales sailing via Rio de Janeiro where the ship briefly sailed in convoy with the male convict ship the Admiral Gambier. Friends arrived at Port Jackson (now Sydney) in October 1811.

Elizabeth married Thomas Buck in 1814 at Windsor; this marriage was short-lived though as Thomas died in 1817 and muster rolls from that year show Elizabeth as a singlewoman. However, by the time of the 1825 muster, it shows her as free by servitude and ‘wife of Mr Hinton at Parramatta’ doing ‘country services’ (general agricultural and dairy work). Elizabeth had married free mariner (and later Parramatta River boatman) Thomas Hinton in 1821 at St Johns Parramatta. Unusually, Elizabeth appears twice on this muster, also as Eliza Hinton, a resident in the female factory, due to the 1825 muster merging together several years at once .Sadly, perhaps this is where she was when she died the following year on 21/09/1826. She is buried in an unmarked plot at St Johns Parramatta as Elizabeth Hinton, aged 46.

Mary Cawson- The Cinder Oven Cook

Mary is a particularly important character to me because she is the link between my last major project on Lancaster Workhouse and my current one researching the women who were transported to Australia as convicts. This is her story…

Finding herself at the Borough Sessions in Lancaster Town Hall (now the City Museum) in 1831, 21 year old Mary, originally from Preston, had only just been released from a 12 month sentence of imprisonment in Lancaster Castle for thefts of turkeys and geese belonging to Lancaster Workhouse, now she was back at the bar for the same crime. Mary was part of a gang of petty thieves who went between the Workhouse, the prison and homelessness, stealing whatever they could, living for the here and now. The gang considered the turkeys which were bred to bring in an income into the Workhouse easy pickings. She was described as ‘an abandoned character’.

Having stolen, butchered and cooked the turkeys in the old cinder ovens near Lancaster Aqueduct, Mary and accomplice William Wharton were apprehended but far from apprehensive during the trial, laughing and joking between themselves. Upon conviction and passing the sentence of transportation for life, Mary thanked the magistrates and whilst being led out shouted “make way for the cinder oven cook!”

After a few months in our castle, Mary was transported to the south where she was put onboard the convict ship “Mary” in June in which she would arrive at Van Diemen’s Land in October. Her ways didn’t change and over the next few years she would repeatedly be in front of the magistrates for disobedience, insolence and absconding from her work, resulting in further jail sentences in solitary confinement.

She married, age 30, later perhaps than other female convicts in 1840 because of her repeated prison sentences, to a fellow convict James Richards at Launceston, though an earlier marriage request to an Alexander Love in 1836 was approved but not seen through and second marriage request to a Thomas Chaplain also in 1836 and again in 1837 was refused. Mary did receive a conditional pardon though it looks possible she died young, aged 37 in 1847.

Alice Tipping- The Sun Street Mugger

Unlike the majority of our previous Lancastrian female convicts who were either opportunistic thieves or simply desperate ones, 23 year old Alice Tipping had a much more vicious modus operandi.

Walking home from work one evening in March 1838, 16 year old clerk William Nevatt was stopped in Market Street by Alice. She grabbed him by the collar before snatching his watch, a gift from his grandfather from his pocket. After a brief struggle Alice ran and William chased her around the corner into Sun St where he tried to get his watch back. William was then threatened with being stabbed through if he persisted into trying to retrieve the watch from her. Crying out ‘thief’ the police came out from the police station on the street and arrested Alice.

Trying to say that the watch was payment for an ‘improper’ transaction did not impress anyone, especially a watch personalised with the initials of both William and his grandfather. Alice found herself at the bar of the castle’s Assizes the following week. She was reminded of her previous convictions and that she had escaped a death sentence thanks to recent changes in the law but would still be sent off to Australia for ten years. Three weeks later she left Lancaster Castle in the company of two male prisoners, also bound for the hulks.

Just one calendar month after the events on Sun St, Alice was aboard the ship John Renwick on a four month voyage to Sydney. Alice worked as a laundress, receiving her ticket of leave in 1845 at Parramatta and married the same year to a fellow convict, Charles Nelson at St John’s. Despite this, she still repeatedly ended up back behind bars between 1847 and 1850 for drunkenness and vagrancy ending with a final four month sentence with hard labour for theft. She was described as 5ft 1 tall with a ruddy complexion, brown hair, grey eyes and a scar on her right cheek. She was tattooed with a man and a flag on her left arm.

Ann Stephenson- The Beaumont Hall Housemaid

Found on Green Lane, on the outskirts of Lancaster, Beaumont Hall was the home of Mr Edward Foster Buckley Esq (who as a local gentleman, regularly sat on the Grand Jury at the Assizes and whose daughter had married into the slave trading Hinde family). In 1815, whilst working at the hall as a servant for Mr Buckley, 17 year old Ann from nearby Skerton stole from Jane Lewis, perhaps a fellow servant, a workbag, silk bonnet and other items.

Ann was convicted of the thefts at the Epiphany (January) Quarter Sessions at Lancaster Castle and was handed a seven year sentence of transportation. After being held in the castle’s dungeon tower cells for six months, Ann and eight other women were taken to Woolwich where they boarded the convict ship, the Mary Anne.

Her description from the convict indent was a follows- ‘5ft 2, slender, a sallow complexion, brown hair and blue eyes, originally from Kendal’.

A gruelling six month voyage brought Ann to Sydney in 1816 where shortly after, she married fellow convict William Birkenshaw who had been convicted at Derby and was almost 20 years her senior.

After living a quiet life in Australia, Ann returned to crime in her later years; she received several sentences of imprisonment in Sydney, one of which, in 1845, was alongside her husband for theft (her) and receiving stolen goods (him). Ann received a further one year sentence, partially in solitary confinement in Parramatta’s Female Factory.

Ann died aged 56 in January 1854 and is buried in St John’s Cemetery, Parramatta, Sydney.

Sarah Todd- The Last Lancastrian Convict

170 years ago yesterday, Sarah Todd arrived at Hobart, Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) onboard the Duchess of Northumberland; the final female convict ship.

Sarah, a married hawker (door to door seller) aged 23 was an interesting character and her case at the Lancaster Castle Spring Assizes in 1852 was well recorded.

Acting as a prostitute, she grabbed a man called Joseph Bunton on Bridge Lane as he left his sister’s house. Pulling him into a doorway, she roughly shoved her hand into his pants, attempting to solicit business, whilst her other hand pocketed his purse with one crown, nine half crowns inside. Declining Sarah’s services, Joseph ambled away, doing up his trouser buttons before getting as far as the bottom of New Road before realising he’d been robbed. Reporting it to the police, despite a change of dress from green to plaid, Sarah was apprehended trying to climb up the steeply terraced slope behind Bridge Lane.

Upon her seven year sentence of transportation, Sarah burst into tears, lamenting the distress it would cause her mother. From the castle, Sarah was transferred to Millbank Prison in London, from where in November that year she boarded the Duchess of Northumberland, the last female convict ship. A five month voyage saw her land at Hobart.

Although there is more to discover about her, we know she saw out her sentence, becoming a free woman by 1860.

Alice Jenkinson- The Untransported Convict

Up to 20% of women sentenced to transportation over the seas never in fact, left the country. Many instead languished in jails either locally or at Millbank Prison in London. A lucky few, even amongst those with life sentences received pardons after several years behind bars. This happened for a number of reasons; the age of the prisoner- either very old or very young, ill health or infirmity, occasionally good behaviour in jail, the threat from epidemics within the jails (such as at Millbank) or more commonly, lack of available transport to Australia.

Alice Jenkinson-, aged 46 was one such woman. Tried at the march assizes in 1836, she had stolen an iron pan with lid from a doorstep in a yard off Penny Street before pawning it at John Thompson’s shop. Having been convicted of stealing a copper kettle and imprisoned in Lancaster Castle just the year before, she received an automatic life sentence of transportation.

However, perhaps due to her age and the slowing down of female convicts being sent to Australia, Alice never did get sent to Australia. In fact, in 1842, now aged 52, described in the Lancaster Gazette as ‘an old offender’, ‘incorrigible’ and ‘wicked and drunken’ she received another 12 month term of imprisonment for stealing clothing from the house where she had been employed as housekeeper.

Old habits never die it seems!

Ellen Eatough- The Convict with Brontë Connections

Ellen, born at Ribchester in December 1806, had got off to an early start. Already at the age of 14 she was serving six months in Lancaster Castle for a theft at Haslingden. She was described as a weaver, with short brown hair, slender build, grey eyes and a burn scar on her left thumb.

After a few years she found herself at Tunstall in the Lune Valley, whether as a servant or working nearby it’s uncertain but from the vicarage of Reverend William Carus Wilson and family in early March 1824, she stole: a cloth pelisse (front closing coat/gown), a straw bonnet, a pair of stays (corset), a silk gown, five pairs of cotton stockings, one pair of gloves, one pair of boots, one silk handkerchief, one stuff gown (one made from a coarsely woven cloth) , one pair of pattens (overshoes for outdoors), one sovereign five shillings, a watch chain, two work bags, a red leather Morocco case and variety of small trinkets. Quite a haul!

Reverend Carus Wilson has earned himself a place in history- he founded the Clergymen’s Daughters School at nearby Cowan Bridge, now famed for educating the four older Brontë sisters (Maria, Elizabeth, Charlotte and Emily) also in 1824-5. The sisters were all removed after the illness and then later deaths of Maria and Elizabeth from TB. Charlotte went on to blame the poor living conditions and health provisions at the school for causing her sister’s deaths and would base her headteacher character of Mr Brocklehurst in Jane Eyre on the evangelical Rev Carus Wilson.

The Lent Assizes at Lancaster Castle followed just a couple of weeks after Ellen’s arrest and she was found guilty of larceny, sentenced to seven years transportation. After a six month wait in the Castle’s cells Ellen was put aboard the Grenada with a group of eight other Lancastrian women, arriving at Sydney in January 1825.

A year after arriving, Ellen married Charles Breaker, a fellow convict from Southampton. In 1827 she ran away from her assigned work and after a short trial received three additional years on her sentence, going into the Parramatta Female Factory. However, she gave birth to a child, James, in the factory in June 1828 and he was baptised at nearby St Johns in August. She was recommended for a ticket of exemption and finally left in June of 1829.

Ellen Hargreaves- The Female Factory Rioter

Ellen Hargreaves was 30 when she found herself arrested and convicted of arranging for two neighbours Ellen and Hannah to steal 4.5 yards of worsted (woollen) cloth and six hankerchiefs from their husbands (Thomas Bramfitt and William Whittaker) for her in Lancaster. She was sentenced at the Lent Assizes at Lancaster Castle to seven years transportation.

After a long 15 month’s stay in the Castle’s cells, Ellen was transported to Woolwich where she was put onboard the convict ship ‘Mary’ along with a group of other women from Manchester. The surgeon onboard the Mary records in great detail how she suffered with six weeks of severe sea sickness, constipation, heavy bleeding after an absence of her menstrual cycle (many women due to malnutrition and stress in the prisons stopped having periods), very painful rheumatism in all her joints and suffered the administations of laudanum, calomel, gentian, blood letting and a hot blister. On arrival at Sydney after a journey of four months (short for the time) she was sent straight to the general hospital.

Two years after arrival and working as a bonded servant, Ellen applied for permission to marry a fellow convict, Thomas Flint (convicted of highway robbery at Hertfordshire). They were married at St Matthews, Windsor, Sydney in October 1825.

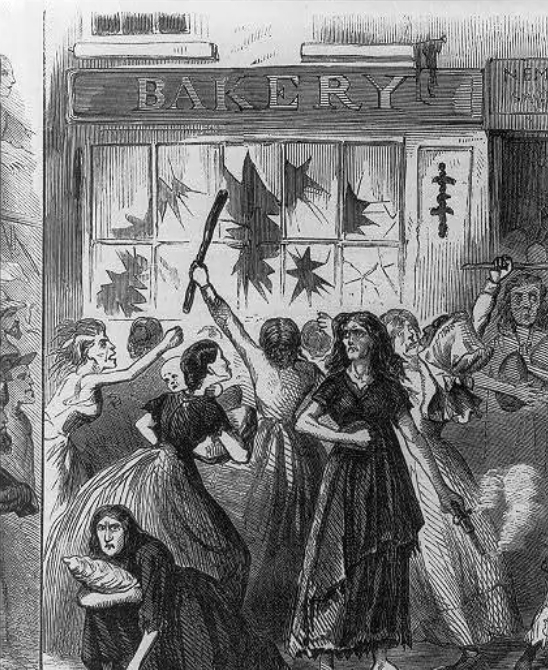

Two years further on Ellen had fallen foul of the law once again and was a prisoner in the Parramatta female factory. The prisoners had been growing increasingly dissatisfied over the reducing food rations and treatment by the matron. The matron herself resigned from her post citing the ‘irksome’ duties she had and a new matron was brought in who immediately cut rations of bread and sugar even further and a riot ensued. On October 27th 1827, around 200 armed women broke down the gates of the prison and charged around Parramatta ‘like Amazonian Banditti’, breaking into shops and taking the food. It took several months to recapture all the women who had escaped. Ellen was said to have been one of the ringleaders that encouraged this breakout. For her part, Ellen received three months in ‘3rd class’, the area of the prison with the harshest conditions.

Despite her tumultuous early years in Australia, Ellen still received her certificate of freedom on 1st April 1829. In her record she was described as being 5ft 2, brown haired, blue eyes and had a fair, though pockpitted complexion.

Eve & Jane Hodgson- The Silverdale Pork Thieves

In May 1804 mother and daughter Eve (age 37) and Jane Hodgson (age 17) were convicted of breaking into and stealing from the home of Daniel Walling in Silverdale, 3 hams, a part of a flitch of bacon, a hogs cheek and 12 shillings.

The Reverend Robert Housman who would go on to build St Anne’s Chapel on Moor Lane had them committed to Lancaster Castle to await trial at the August Assizes.

They were found guilty. Jane was sentenced to 12 months imprisonment with hard labour in Preston’s House of Correction. Eve bearing responsibility was sentenced to 7 years transportation to New South Wales.

After waiting in the castle’s cells for 11 months, Eve, along with nine other convicted women, was put on a cart, shackled to it and driven the 315 miles to Spithead off Portsmouth where she was put aboard the convict ship, the William Pitt for a nine month voyage and a new life in Australia, arriving in April 1806.

As Eve arrived in Australia, back in Silverdale, Jane once again stole some money and in the July Quarter Sessions at the castle was sentenced to the same fate as her mother. Jane was transported onboard the Speke arriving in Nov 1808. Mother and daughter were reunited as both can be seen together on 1811 and 1820 muster rolls. As you had to turn up to these rolls at a given day and time and queue up to give your name, the fact that Eve and Jane appear together in an otherwise unassorted list of thousands of settlers tells us they not only reunited but stayed together for many years. The latest record for now, is an 1822 muster which shows only Jane, still unmarried and now free by servitude, living at Windsor on the outskirts of Sydney.

The Storrs Family- Melling Milk Thefts

The Storrs family lived at Melling, just up the Lune Valley. Documents show the family in poverty, getting thrown out of nearby parishes for becoming a burden on the ratepayers. Times were clearly hard enough for Mary, age 52 and her adult children Ellen, 30 and Edward, 18 who stole milk. All three were arrested and sent to the Quarter Sessions at Lancaster Castle in October 1800. Found guilty, the family were each sentenced to 7 years transportation.

The family awaited the long journey to the south coast in the gaol at Lancaster Castle. Ellen was sent first in May 1801 along with two young Manchester women; she was given £2 and 13 shillings to buy clothes and provisions for her new life and was put aboard the Nile, a ship which travelled in convoy with two other male convict ships. It left English shores in June 1801, arriving at Port Jackson (modern day Sydney) six months later.

Next to go was Mary in September 1802, she was sent along with a number of other prisoners and put aboard the Glatton which transported both male and female convicts, her journey to Australia via Rio de Janeiro also took six months, arriving in March 1803.

Edward was the last to leave Lancaster. In April 1803, he was sent to the prison hulks moored at Woolwich where he was held onboard the Retribution. A different turn of fate though meant he was offered a pardon in January 1804 on condition he served in the army.

In Australia, Ellen soon found herself pregnant to fellow convict John Gost, having a child she named after her brother, Edward. No marriage took place between Ellen and John. By 1805, Ellen, now a washerwoman had married a John Holmes, a carpenter and now free, former convict. The years passed, relatively peacefully and by 1825 we see mother and daughter living together again, all now free by servitude. Mary married farmer George Gamble or Gambling in 1818 when she was around 70, living to the incredible age of 92.