Here I regularly post my own research, stories and articles about people, events and places in the local area.

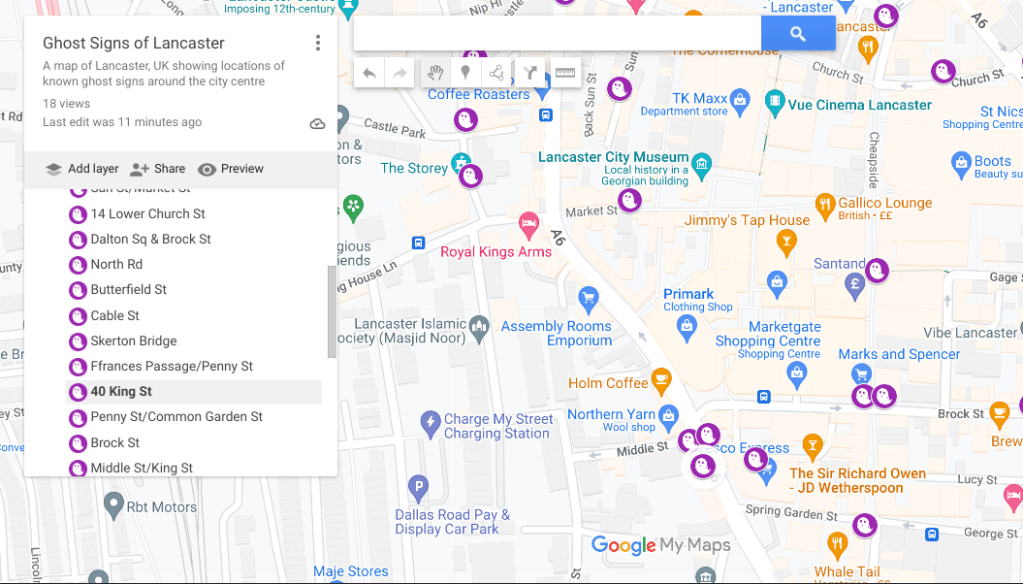

Ghost Signs of Lancaster

Today is Halloween, so what better time to launch the map that I’ve been working on that locates all the ghost signs (historic remnants of painted signs, adverts and names) in Lancaster. The interactive map shows all (current) known ghost signs and photos where possible.

Click the screenshot below to head to the map….

Locating the Lancaster Gallows

Prior to 1800, executions took place in public on Lancaster Moor. Locals have long

speculated where exactly those executions took place.

Although the appropriately named Golgotha and the highest point of Williamson Park seemworthwhillocations for consideration, maps such as Yates’ 1786 both depict and place the

gallows within the triangle of land formed by Quernmore and Wyresdale Road, almost

opposite Highfield with the quarries (now Williamson Park) above the site.

This then places the gallows on the land now owned by Lancaster Royal Grammar School

as their upper site but can we narrow the location further?

A key piece of evidence comes from the writings of local historian ‘Cross Fleury’ in his 1891

work ‘Time Honoured Lancaster’. In it, he talks about the tragic execution of poisoner Mary

Hilton who was strangled and burned (supposedly still alive) for murdering her husband in

A memoir within the book, recorded in 1825, states that Mary’s execution “took place

opposite the second window of the north of the workhouse”. This is problematic though;

Lancaster’s workhouse was not yet built on Lancaster Moor (building began 1787/88).

However at the time the memoir was recorded, the workhouse had been built but was still in

its small, earliest central block format (see Binns’ 1821 map).

“the mayor, &c., do give and grant liberty to erect a proper and

convenient poor-house on a piece of common ground on Lancaster

Moor, betwixt the two highways there, near to the stone quarries…”

Lancaster Corporation announcement. 1787

If we know then, that for a period of 12 years after, both the workhouse and executions were

in operation on the same location concurrently, this almost certainly meant that the paupers

of Lancaster Workhouse (particularly the male inmates whose dormitory windows faced the

place of execution had the misfortune of observing the 30 or so hangings that took place

during this time.

The choice of this land for building the workhouse on is perhaps not a surprise, it was after

all corporation-owned common land on the edge of town. The land was described as

“healthfully and pleasantly situate on the side of Lancaster Moor” and its size allowed for

future expansion of the workhouse site- a consideration due to the increasing town

population and the trend for moving prisoners, paupers and lunatics (sic) to less publicly

visible sites on the edges away from towns. Conversely, executions would be more fittingly

held at Lancaster Castle; the place of conviction and incarceration rather than the spectacle

and effort of taking everyone up onto the moors and trampling through the new workhouse

site. Furthermore, whilst the powers that be were not necessarily always kind to the poor,

there was some degree of sympathy and holding executions in full view of the deserving

poor would not have been considered appropriate.

Early site plans of the workhouse from the 1820s and 1840s overlain over modern maps of

the Lancaster Royal Grammar School site now allow us to pinpoint a much smaller area

where death sentences were carried out. By overlaying the 1840s town plan of the

workhouse over a satellite map of LRGS we can project a line outwards from the ‘second

window from the north’ as recorded by Fleury (obscured by this stage by 1840s workhouse

expansions). Somewhere along this line is our mark. It is notable that this line follows the

historic boundary line between the moor and the town lands.

orientated towards second window from the north as recorded in Fleury

Before making a firm assumption though, based on memoirs and secondary evidence we

should question if the site of execution was fixed; could there have been a number of

different sites around this area? This is a perfectly legitimate argument and is certainly still a

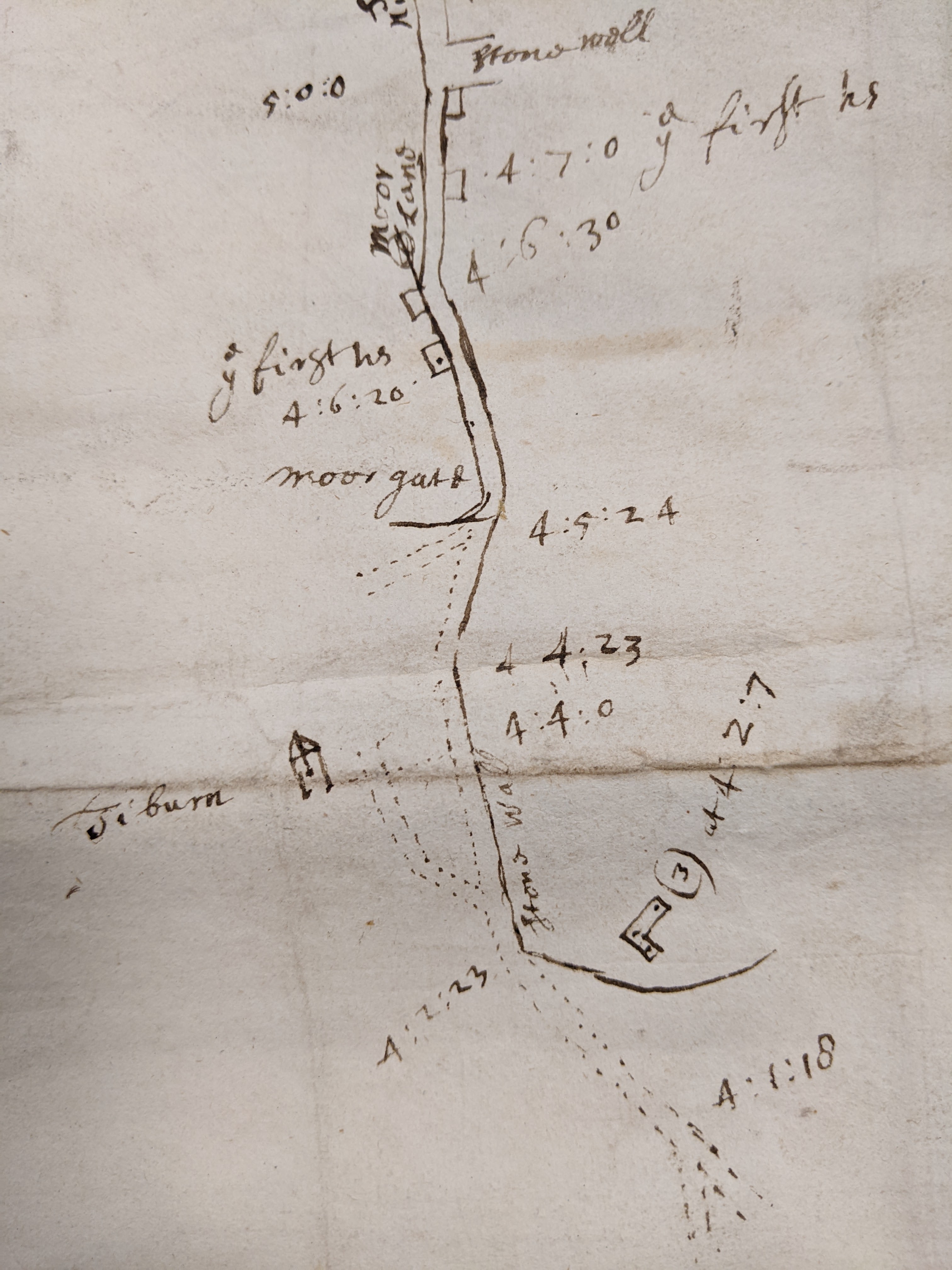

possibility when we go even further back in time. There exists a contemporary map, not wellknown, which confirms that the execution site was still the same 100 years earlier. A map,

attributed to Richard Kuerden from 1685 gives a highly detailed and accurately surveyed

view of the town and beyond as he took measurements walking from the top of Clougha all

the way into Market Square in miles, furlongs and poles; passing by the gallows and marking

their location on the moor.

DDX 194/26. Lancashire Archives.

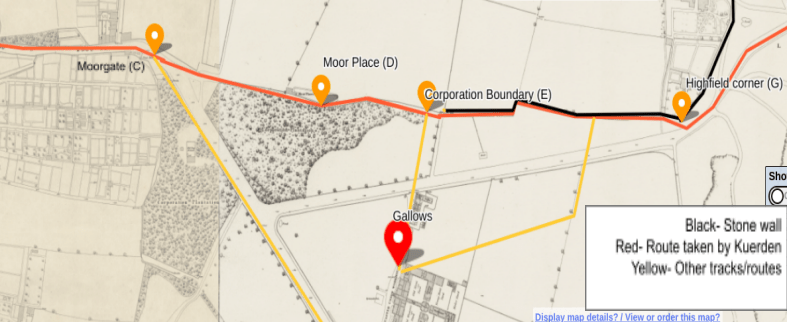

It is admittedly tricky to align this map as no other detailed contemporary maps exist of this

area at this time, but using the back wall of the Highfield estate as a fixed point (G), along

with Moorgate (C ) which was the literal gate onto the moors as marked on Binns’ 1821 map

being almost at today’s junction with Ullswater Road and the historic points of the old town

boundary (E) and the dip in Park Road where Moor Place Farm was (D), we can overlay

again on a modern map. Following the route as someone on foot (rather than as the crow

flies) and conversion of the furlongs and poles into metric measures of distance corroborates

these as the correct points. This of course reveals a slightly different route to the moor than

today. After passing by ‘ye first houses’, roughly where the canal and Moor Lane intersect,

you would climb uphill, as now, passing through the Moorgate. Though the road to the east

(Wyresdale Road) existed, Quernmore Road did not in the 1600s and even 100 years later

would still only be a minor lane), instead, you climbed a track, along the modern line of Park

Road, which still has a historic right of way at the top, crossing the town boundary (just

before the modern line of Derwent Road) and coming to the edge of the Highfield estate

which was bordered by a stone wall. The route cut across today’s Highfield recreational field

(previously the Workhouse Green but then just moorland). Finally, a further small track bent

back to the place labelled on Kuerden’s map as ‘Tiburn’. Tiburn had become synonymous

with gallows due to the well known London gallows of that name.

Kuerden himself described this area in his notes as thus- “and going through Scotford

(Scotforth)Town[…] half a mile further you come to the Moor leaving on the right above the

gallows an ancient seat call’d the Highfield. Here is a fair prospect of the town and castle,

entering into a little lane, leading into the town straight toward the castle…” (Earwaker. 1876)

map. NLS maps/ OS 1840s town plan

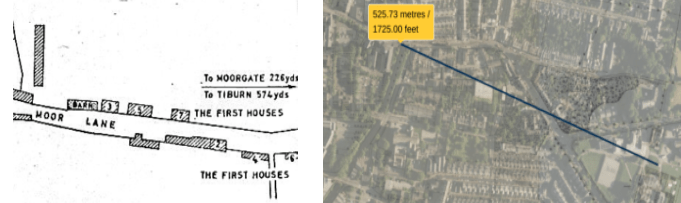

We can also check against Kenneth Docton’s 1958 recreation of the Kuerden maps. In it he

shows from his lightly shaded box on the extreme right of the map ‘Tiburn 574 yards’ pointing up

Moor Lane. As the crow flies there are indeed 574 yards (525m) from the first houses to the

gallows site.

NLS maps with distance from the sites of the first houses to the gallows

Kuerden did not take a measurement from point (E) to the gallows and unfortunately his scale, drawing by hand, varies between 1mm on the map equating to 8-12m in real terms. However, using the defined edge of the workhouse building in 1788 as an end point, the evidence from Fleury and Yates and an average of 1mm on the map = 10m (14mm/140m from (E) to gallows) we are much closer to locating the spot.

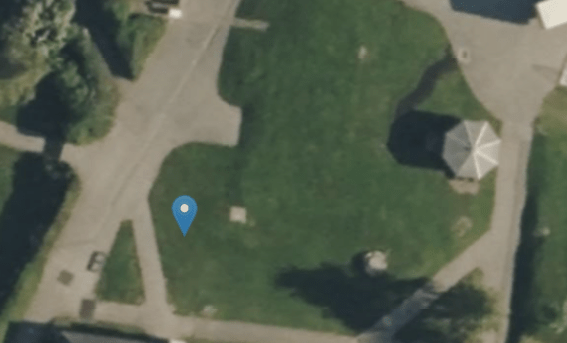

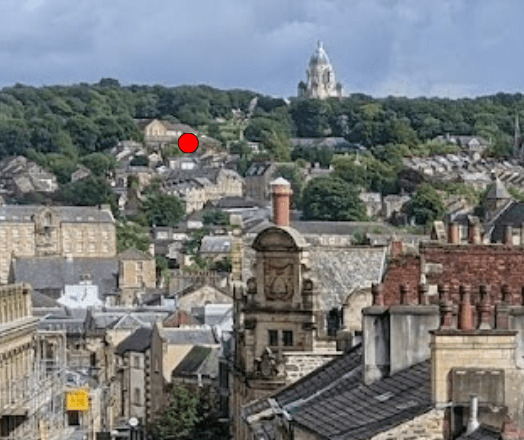

To close, we can now pinpoint with some accuracy the location of the Lancaster gallows within LRGS grounds. The evidence places it in a grassed square near the electrical block (ironically a mortuary during the 19th century workhouse years) the modern school medical centre in Storey House and the Timberlake building. A newly built timber framed pavilion/shelter sits nearby the site today.

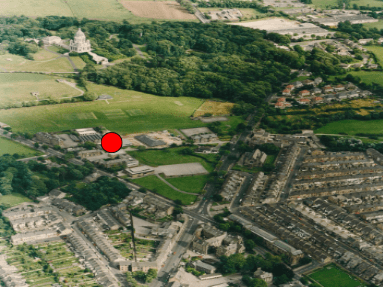

Aerial view during workhouse demolition 1960s. Lancaster City Museum

Notes on Kuerden’s Measurements

8 furlongs:1 mile

40 poles: 1 furlong

All measurements are from point to point on foot, distances were measured from Clougha Beacon to Lancaster Market Cross

Moorgate (C) to back Highfield wall (G)- 121 poles (608.5m).

Back Highfield wall (G) to town boundary (E)- 57 poles (287m).

Town Boundary (E) to Moor Place (D)- 23 poles (116m).

Moor Place (D) to Moorgate (C )- 41 poles (206m).

With grateful thanks to John Rogan at Lancashire Archives and Gregory Wright of Lancaster Walks Talks & Tours for their assistance.

Lancaster’s Titanic Connection

Chief Steward

Titanic sank 111 years ago this month but did you know that a Lancaster man was a crew member onboard? 1st Class Chief Steward, Andrew Latimer was sadly lost along with over 600 other crew members in the 1912 sinking .

Andrew was born at Castle Cottage on Castle Hill (presumably part of the group of cottages that originally fronted the castle, demolished in the 1870s) on 31/1/1857 and was baptised soon after at St Mary’s (the Priory) by his parents Robert and Margaret. As a railway porter, the nearby Castle railway station must have been handy for his father. They didn’t stay long though and less than two years later had moved to Orton near Tebay.

Moving to Manchester as a victualler and later working for shipping lines, Andrew moved up the ranks. After working on numerous ships and having a large family of his own, he worked on White Star Line vessels such as Olympic and Teutonic before his final voyage on Titanic. As chief steward for the first class passengers, Andrew’s role was to oversee all the other stewards, particularly within the dining saloons.

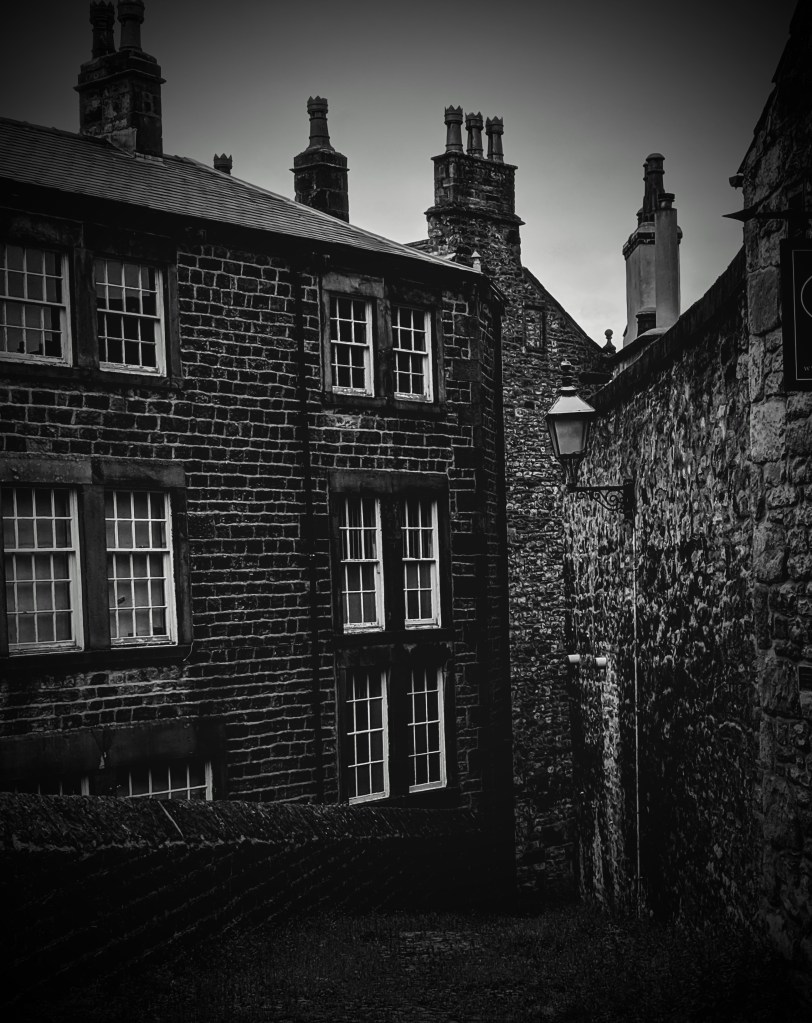

A Castle Hill Haunting?

The story that follows is based on reports from the Lancaster Guardian in 1969. Don’t go up Castle Hill after dark…

A family living at the foot of Castle Hill began experiencing strange occurrences often in the late afternoon in autumn 1969. A creaking sound could be heard on the first floor and doors opened and closed for no apparent reason. Lights switched on by themselves and their cat would suddenly not go upstairs. The female residents of the house began to feel increasingly uneasy, like they were being watched.

Lying in bed late one evening, the owner who had her relatives staying with her, saw the bedroom door opening in front of her. Expecting to see her niece or sister, she was frozen to the bed when she saw a disembodied finger hovering in the doorway. The finger, which had a long curved nail, floated across the room towards the bed and its terrified occupant until it disappeared just before reaching her. Dismissing the horrifying event as a nightmare, the woman didn’t say anything.

A few days later, on a dark, rainy afternoon, the woman and her sister had gone out on an errand leaving the young niece at home alone. The niece was helping her aunt by cleaning the stone stairs for her. Mopping the stairs, she suddenly had the feeling someone was standing in front of her. Looking up, she came face to face with the same floating finger with its long straggly, curved over nail which was pointing through the banister. Screaming, she dropped the mop and bucket and ran.

Only the very next day, the spectral finger again appeared to the niece as she once again saw it floating down the stairs, it passed close by the terrified girl before going into the living room. This time, her own mother was in the house and next door neighbours were summoned but nothing could be found, but the lights had mysteriously been turned on in the living room.

The final time both daughter and mother were sitting together, watching television. Both looked up to see the door open but only the daughter saw the finger coming towards them. The daughter watched in horror as the eerie finger poked her mother on the shoulder; the mother, seeing nothing, thought her daughter had nudged her. Enough was enough and mother and daughter packed and left.

The next day, the homeowner, seeing her bedroom door opening and closing by itself had had enough- the vicar of the Priory Church just up the hill was called to bless the house.

And that dear readers is where the story ends, for no further reports in the local newspapers were made. Whether the family moved out or the hauntings stopped, we don’t know but the story went down in local Lancaster folklore, well into the 1970s. As with all good stories and especially amongst local school children, the details changed over the years; the finger was green, it had a two foot long nail, it was from a child employee of Gillows who had lost their finger in a horrible accident. Later on, it ‘moved’ and was now terrorising people around Dalton Square (attributed to Dr Ruxton, naturally), if you felt a tap on your shoulder- death would soon follow- the variations on the story were endless.

Perhaps you remember this particular ghost story being told or other local spooky stories. I’d love to hear your tales. Happy Halloween!

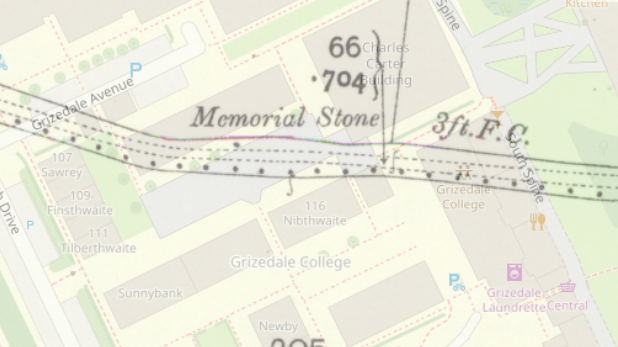

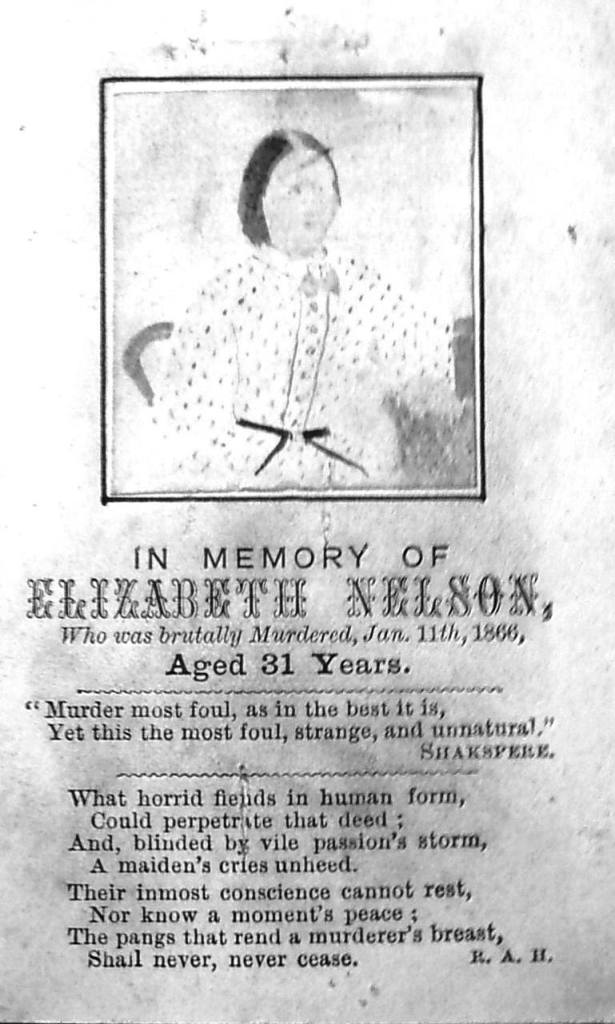

The Green Lane Murder, Scotforth 1866

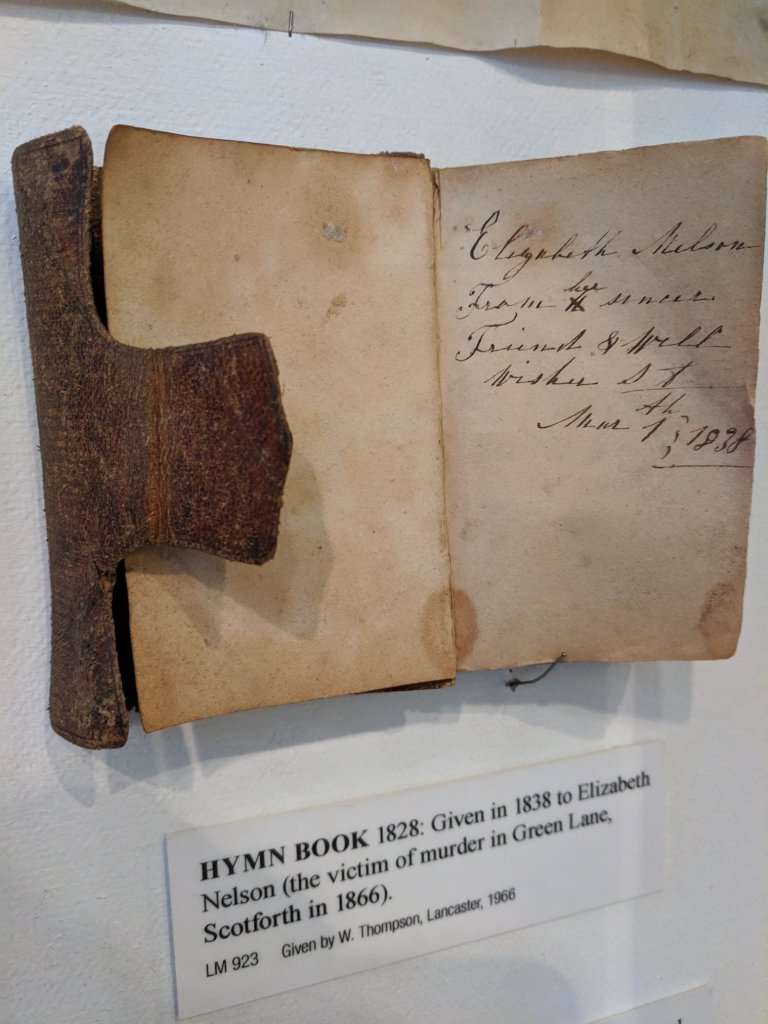

On a winter’s evening in January 1866, 31 year old housemaid Elizabeth Nelson set off from Richmond House on Slyne Road where she worked to deliver a bonnet and a letter. She was never seen alive again. The next morning, on a remote back lane between Bailrigg and Ellel her body was found. She’d been strangled to death with clear signs of both physical and sexual assault. Quite rightly, the inhabitants of Lancaster were greatly disturbed, both at the brutality of the crime and that no-one was ever convicted.

Elizabeth had been born just outside Kirkby Lonsdale, coming to Skerton, Lancaster with her mother Mary at a few months old. Mary began working as a servant/ housemaid at a young age, working for the Jolly family for many years and settled in Skerton with her mother where the Nelson’s made their home.

By January 1866 Elizabeth had been working for the Whalley family of Richmond House for just under a year when she decided to set out in the dark. She had discussed posting a letter in town which had been waiting on the side table all week, when she left the house around 5.30pm. The letter she took contained a bill and was for George Miller who lived at Burrow, between Scotforth and Galgate. It had been incorrectly delivered to Richmond House, instead of to the farm owned by her employer, Mr Whalley at Burrow where Miller worked. Initially, other household staff would comment that it seemed strange that Elizabeth would hand deliver this letter when it could have been taken to Skerton or even Lancaster post offices. Enquiries would later reveal that Elizabeth had been courting George Miller, who worked as a farm labourer at Burrow (now known as Burrow Heights Farm). Delivering the letter personally would have allowed Elizabeth to have met up with her boyfriend. The bonnet which she also took, was firstly delivered to an address in Middle Street in the town centre and belonged to Mrs Rebecca Barrow who was sister to her fellow housemaid Ann Williamson. After a moment’s visit, Elizabeth left. Mrs Barrow, the homeowner, was the last definite witness to see Elizabeth alive.

Elizabeth was heading to Burrow, a distance of two miles south from Lancaster. Despite the darkness, the hour wasn’t especially late and a number of people were walking along Greaves Road and the turnpike that evening, though none could definitively recall seeing Elizabeth when questioned at the inquiry. The only possible sightings were from Mr Welch, of Burrow House who was returning from the Boot & Shoe with his horse and cart around 7pm when his horse whinnied and he was aware of a black clothed figure standing just by the two mile marker stone. The other was from a Master Bleasdale who was standing at the gates to Mr Paley’s property at The Greaves when he thought he saw a woman all in black, with a veiled face and a plaid shawl. This did accurately match the clothes Elizabeth had been wearing that night, the shawl had been borrowed from her fellow housemaid at Richmond House. Her almost colourless outfit could well have been the reason so few people saw her that night.

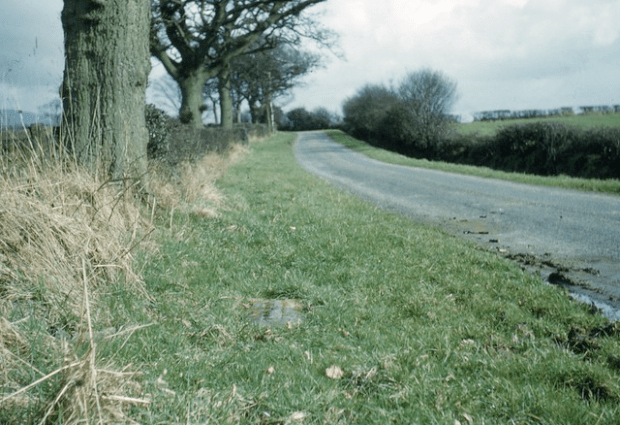

The lane where Elizabeth ended up was over half a mile further on and on the opposite side of the turnpike to Burrow where she had been heading. Elizabeth had only been to Burrow once before, in daylight the previous summer and it was uncertain whether she had lost her way in the dark and either ran up or was led up the track locally known as Green Lane or Barrow Green Lots Lane which connected Chapel Lane to Hazelrigg Lane. Both were quiet rural routes that provided a shortcut between Ellel and Bowland to the turnpike. The only features in this track were small gravel pits. Even in its day, the remote Green Lane was described as overgrown and little used.

Just over a mile away around 7.30pm in Ellel, silk spinner James Beck heard a woman’s screams coming from the direction of where Elizabeth’s body would be found. His dog began barking as the scream abruptly ended. Just over an hour later, snow began to fall.

The next morning around 9am, Elizabeth’s body was found in the snow by farm worker Thomas Wilkinson. Wilkinson raised the alarm with nearby farms and the Galgate police were alerted. Elizabeth’s arms and lower half were covered by snow though it had melted due to her retained body heat on the top half. There was no snow under her, revealing she had died before it had begun to snow about 8.45pm the previous night.

It was over 24 hours after her disappearance when concern for Elizabeth’s whereabouts grew at Richmond House in Skerton that Adam Lund, the stable groom after enquiring at her mother, Mary Nelson’s house at Skerton went to Skerton Police Station to report Elizabeth as missing. Officers revealed to him that the body of a similar aged woman had been found early that morning in Scotforth and Lund went directly to the Boot & Shoe public house where Elizabeth’s body had been taken, positively identifying her before presently returning back to his employers on Slyne Road.

The letter she had meant to deliver to George was found some time later by John Baines of Bigforth Farm, close to where Elizabeth’s body had lain as well as some false teeth which she had worn.

At the coroner’s inquest and then inquiry that followed the key suspects in the case were two local farmer’s sons; John Cottam, aged 24 of Five Ashes Farm and his friend Joseph Dunderdale, aged 20 of Burrow Farm. They were and potentially still are, the most likely culprits that were arrested and questioned though both were later released. They lived on neighbouring farms and could not give accurate or corroborating accounts of where they (Cottam especially) had been between 7pm and 8pm the night of the murder. Dunderdale had made two short visits during this time to see his girlfriend, Jane Procter at Burrow Beck Farm (the discoverer of Elizabeth’s body, Thomas Wilkinson, also lived and worked there). Their discrepancies in accounting for all their time out of their homes that night did give time (for Cottam) to have committed the murder, though when he came to visit nearby Burrow House at just after 8pm, he appeared neither dishevelled nor changed from his usual character in the opinions of the farm workers he spoke with. They did however say it wasn’t usual for him to turn up there and speak with them. During his later examination, some unexplained blood stains were found on a handkerchief and in the seat lining of his trousers though experts could not say with any confidence whether these were human or animal or likely to have been caused by the scurvy from which Cottam suffered. When repeatedly questioned, Cottam claimed not to know Elizabeth Nelson personally, though details later emerged through Elizabeth’s friend Ellen Cleminson that John Cottam had met Elizabeth before and they had all attended a local town dance at the Cross Keys together. Elizabeth had declined to dance with John but did stay at the dance with him after Ellen left. It also emerged later that Elizabeth turned Cottam down after he tried unsuccessfully to court her, saying she much preferred George Miller. Dunderdale confirmed he had previously met her at Richmond House. In addition, as landowners for the Scotforth parish- both Cottam and Dunderdale’s fathers sat on the inquest jury that was held at Scotforth Primary School. After his arrest, Dunderdale was bailed by his own father. Elizabeth’s boyfriend, George Miller was never a real suspect in the case as he remained at Burrow all evening as testified by the Gornalls who he lived there with. Cottam was held on remand at Lancaster Castle for over three weeks and was brought to the Town Hall inquiry four times before the magistrates finally agreed there was insufficient evidence against him to proceed to a criminal trial.

For a time even the police sergeant, John Harrison who was summoned to the crime scene was implicated; he made the damning mistake of requesting Elizabeth’s body be taken away and washed by three local woman at the Boot & Shoe, before any medical professionals or other judicial officers could examine it, potentially washing away any evidence. By the time Sergeant Harrison had been to inform the coroner, his Superintendent and Dr Hall, a surgeon who would perform the post-mortem later that evening, it was 2.30 in the afternoon and the body had been stripped of all clothing and all bodily fluids washed away. This was a huge mistake for a policeman of over 20 years and it was many months before he was finally vindicated though no doubt demoted for his negligent decision that morning.

At the inquest, it was revealed what had happened to Elizabeth that night. Elizabeth’s underskirts were soaked in blood and the two women who had cleaned her body described how she had had blood down her thighs coming from her genitals. More visibly, she had large bruises over both eyes and the top of her head with blood from her temples, nose and mouth as well as others on her arms, thighs and groin. A handkerchief had been double knotted around her neck, though not to the degree that it alone could have strangled her. The coroner noted that she had been penetrated by a blunt object which had perforated her posterior vaginal wall. Her thyroid cartilage had been crushed, suggesting that she had been strangled with pressure from the thumbs and potentially from a left hand. That and the blows to the head had caused her death. The bruises on her arms and dirt on the backs of her gloves show that she had had her arms pinned down to the ground. All this suggested to a number of the experts that a second person could have been involved in the murder.

After the murder, by public subsciption, a benefit fund was raised for Elizabeth’s mother Mary and a memorial stone was made for Elizabeth (the stonemason initially refused to accept payment for it) and in late March of that year it was placed on the spot where Elizabeth’s body was found on Green Lane. Mawkish visitors quickly stripped the surrounding trees and bushes of twigs and branches as souvenirs. The lane itself became devoid of greenery due to the literal sea of human traffic to the site, though a spade mark was made where Elizabeth’s head had rested and this spot remained untrodden. This site of the memorial plaque was marked on OS maps of the time and could still be visited until the 1960s when Lancaster University began developing the land all around Bailrigg and Hazelrigg. Today the memorial site is no longer a quiet bylane but is the heart of the campus of the University. Grizedale College and the area immediately fronting Grizedale bar is today the location of the memorial stone where it can still be seen on the side of a large stone planter. The chapel lane, as it was then called, leading off the A6 up past Lancaster House Hotel and into the University campus is now called Green Lane in its entirety. Behind Grizedale College, a final section of the original tree-lined Green Lane remains alongside the George Fox Building. It is eerily incongruous amongst all the other contemporary university buildings.

Elizabeth was buried at St Saviours, Aughton near Halton on 15th January 1866. Her mother Mary is buried with her.

Despite rewards for information leading to the capture of the culprit/s no one was ever found guilty of the crimes. It later emerged that another attempted rape and assault of a servant girl had taken place on the chapel lane on October 20th the year before. The description of the attacker was of a small man in dark clothes with a brimmed hat. He had grabbed her round the neck. This was not the first such attack; Margaret Townson of Scotforth Mill was attacked whilst heavily pregnant whilst going out early morning in July 1860 to see to the cows. Her attacker was a well known scoundrel, William Green or ‘Cocker Green’ (aged 23) who had held her by the throat while attempting to rape her. He was a well known poacher who knew all the fields and rural areas around Scotforth, Ashton and Wyresdale well. After the attack he was imprisoned for two years at Preston.

Postscript Notes-

John Cottam was killed in his job as a horse breaker in 1889, aged around 47.

George Miller married a previous girlfriend in Garstang five months after Elizabeth’s death.

The ‘boggart’ house which is mentioned frequently throughout the case refers to Oubeck House (now Oubeck and Chadderton Cottages) on the opposite of the turnpike (A6) to the junction of Chapel Lane (now Green Lane).

An interesting feature of the case highlights the inconsistencies in how time was measured locally. A detailed minute by minute account of all the key witnesses as well as the timeframe of Elizabeth’s last journey was undertaken and what becomes clear is that almost all recipients had their clocks set to different times, particularly in the more rural Burrow and Ellel localities. The mill at Ellel, the farms at Burrow, ‘town time’ and ‘railway time’ all refer to a different way of measuring the time. This is despite the railways introducing a standardised way of measuring the time almost 25 years prior. This no doubt involved a huge additional headache to those trying to to work out the timeline of events in the case.

Sources

Lancaster Guardian, Lancaster Gazette, Preston Chronicle

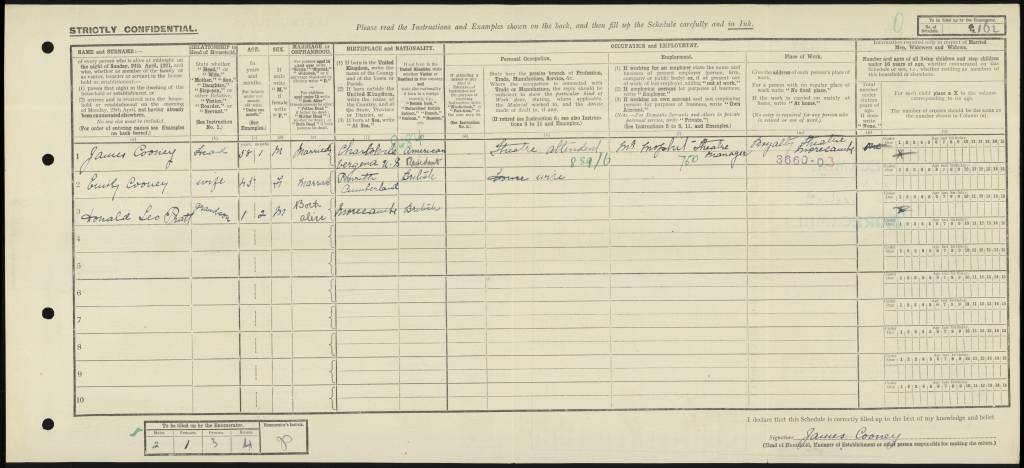

Jimmy Cooney “he brought the sunshine of Virginia into Morecambe”

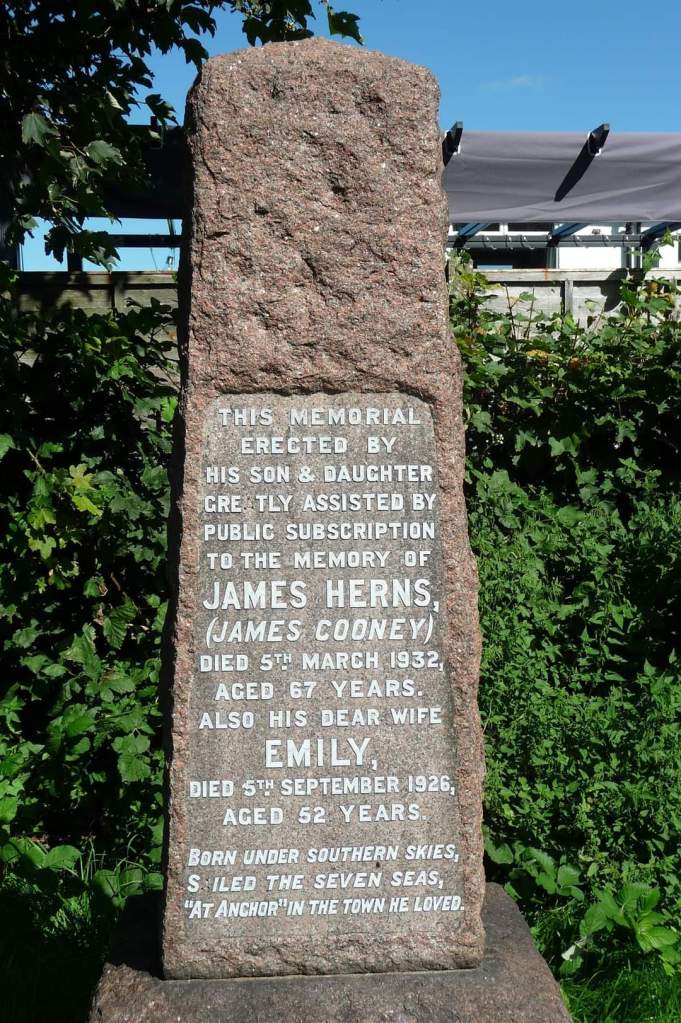

‘Born under southern skies, sailed the seven seas, “at anchor” in the town he loved.’

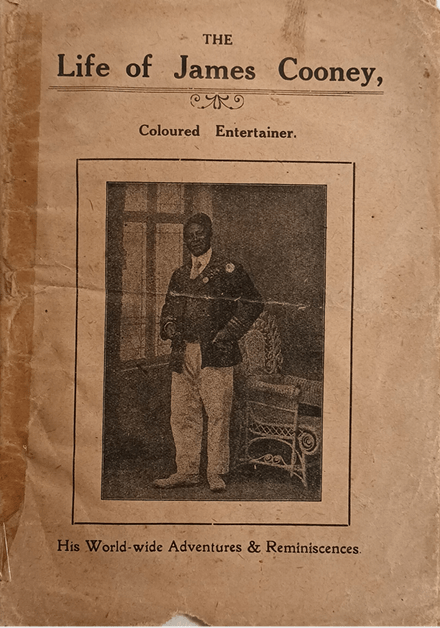

This piece, which I originally wrote for Lancaster City Museum in 2020, uncovers the fascinating life of Black performer, Jimmy Cooney (born James Herns) who after a life of wanderlust and incredible ups and downs found his peace in Morecambe. Although there were a few references to his performing career in other sources there had been no contemporary research into his life before arriving in Morecambe. His incredible story, born under the shadow of slavery and more importantly recognition was fully deserved of being heard…

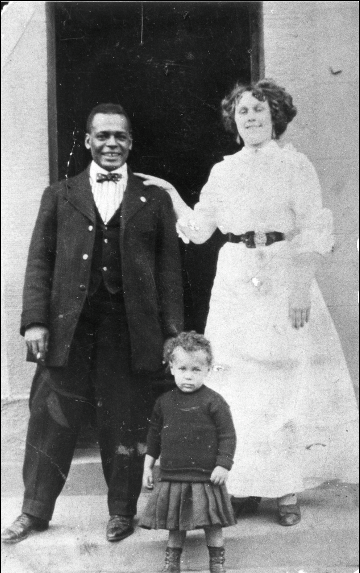

James was born in Charlottesville, Virginia in the USA in 1867, his parents had been given their freedom just two years before after the 13th amendment to the constitution made slavery illegal. James had six brothers and sisters but could only remember his youngest two, his older brothers and sisters had all been sold into slavery; his own mother had been sold twice to the owner of a vast tobacco and sugarcane plantation. James grew up on the plantation where his now ‘free’ older brother, sister and mother still worked for a pittance. When his mother died when James was aged around 10, his life took a new turn.

To survive, James turned to errand running and message delivering where in the process met a Mr Moore, an Irish man who offered to take him back to Ireland. At the age of 12, they set sail on a White Star Liner from New York to Queenstown. At this stage James was handed over to the employment of a Tipperary gentleman and lived as a servant within the household. By 16, James had had enough and like the old adage, literally ran away and joined a travelling circus. He would continue with the life of performance and entertainment in some form for much of his adult life.

After a short time, he again left the circus and stowed himself away on a ship bound for Liverpool. Homeless and without options, he began an unsuccessful career as a sailor crossing the Atlantic to South America, back to Sardinia, to Gibraltar, where he briefly joined the company of other young black men in a performing troupe before again spending a number of years sailing and travelling from country to country, working as a clown, a waiter and even unsuccessfully trying to pass himself off as a well known boxer. More years of travelling around Europe, this time in music halls followed before settling in Morecambe.

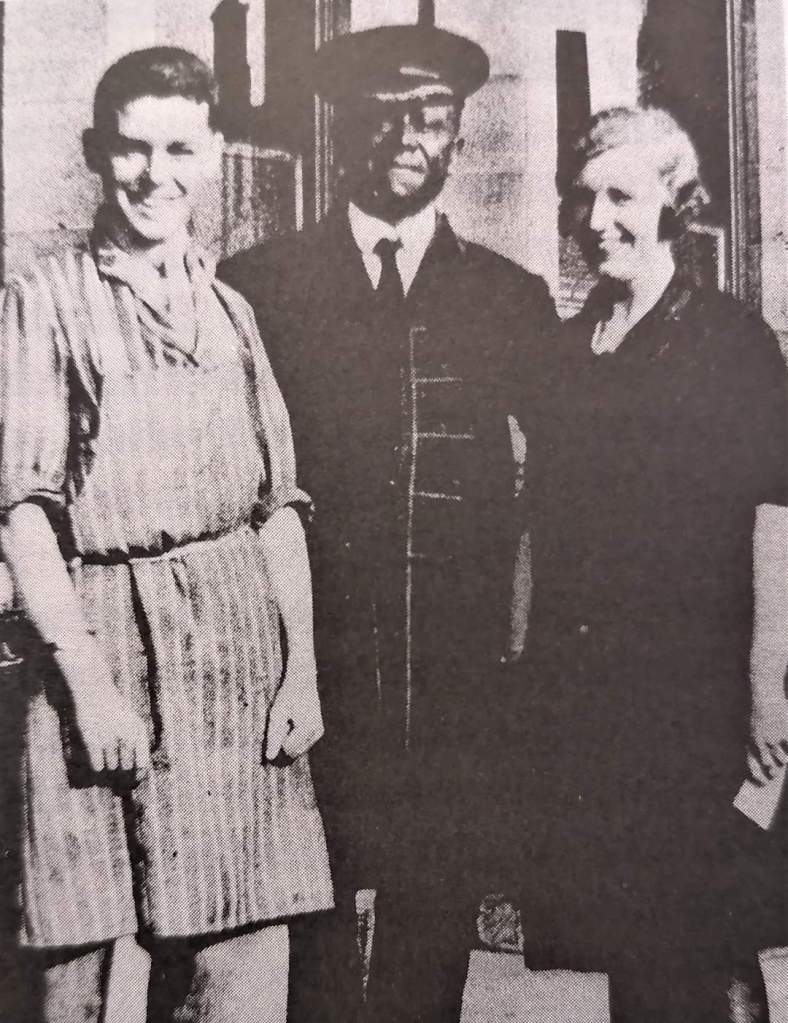

He initially performed with a troupe of other young black men, as well as performing as a pierrot/clown and a holiday snapshot photographer in the West End of the town. In 1898, he married Emily Nicholson at Poulton Le Sands Holy Trinity Church, going on to have two children together, Bella and James.

In more advanced years, Jimmy became a well known face at The Royalty Theatre, Market St in Morecambe and worked for them for many years as a commissionaire. He was extremely well liked and respected in the town. When he passed away from pneumonia in 1932, his funeral procession from his home on Tunstall St was crowded all the way to Torrisholme Cemetery where he was buried with a headstone raised by subscription after an appeal by the owner of the Royalty Theatre and his children “in order to provide a lasting memorial to the memory of a good townsman”.

A Short History of Racecourses in Lancaster

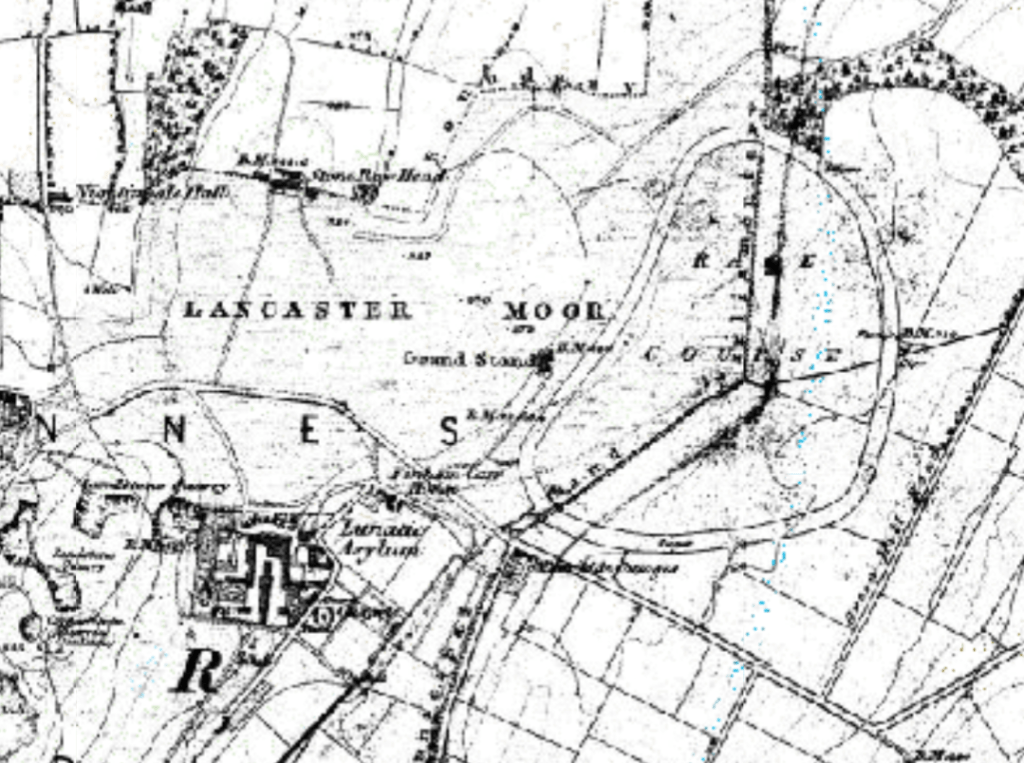

To find the nearest racecourses now, you’d have to head to Cartmel, or even Aintree but for 125 years, Lancaster had its own, very popular racecourses…

The first course was situated on Lancaster Marsh and the very first race was held in 1732 with a 50 guinea prize. The winning horse named ‘Whittington’ was owned by Mr Rawlinson (Lancaster’s principal merchant in the West Indies trade; trading in slaves and exotic woods). The course was extremely popular but due to the enclosure of Lancaster Marsh and the rising crowds a new location had to be found and in 1809, a brand new course was opened on Lancaster Moor. This course sat behind where the Moor Hospital Annexe (now known as The Residence) can be found and goes across the M6 motorway.

For many years, the newspapers of the time talked about the popularity, quality of the horses and riders and the large number of meetings and prizes taking place at the course that drew crowds from across the north west. However by the 1840s, horse racing was becoming less popular and the crowds were thinning so as a way of enticing people back a grandstand was built on an embankment (behind the Moor Hospital Annexe) in 1848. Sadly, this still didn’t draw the crowds in the long-term and the racecourse closed after the final race meeting in July 1857.

The Lancaster Guardian on the 11th July reported that very few horses raced, the attendees were mainly from town rather than pulling in crowds from around Lancashire and that those that did attend were ‘roughs’… who were not to be courted’ and ‘every kind of gambling dodge was in full swing’. In typical Victorian fashion, the racecourse, full of ‘immoralities’ no longer had any place in Lancaster.

The site of the old Marsh Racecourse was later built upon by Lune Mills and extends under what today is the Lune Industrial Estate, modern housing developments and Freeman’s Pools nature reserve. Development of the County Lunatic Asylum (Moor Hospital) Annexe and later the M6 motorway cut through the old racecourse on the Moor but did you know that LiDAR scanning still reveals much of the course? See if you can spot it…

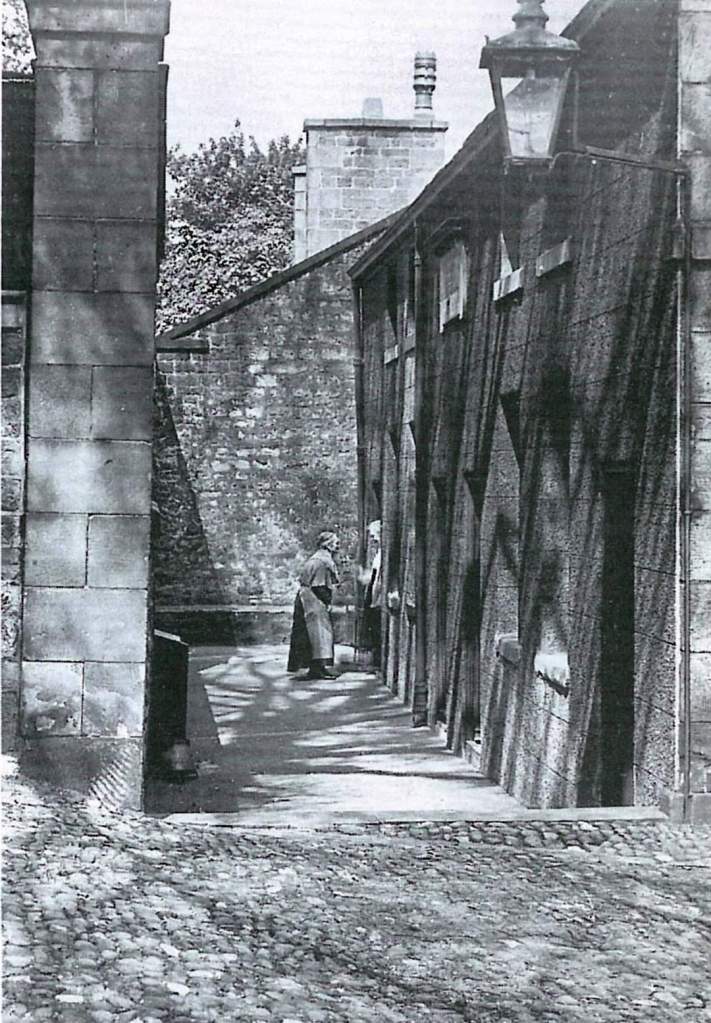

A Helping Hand- Almshouses in Lancaster

In an era when there was no social security safety net, those in need of relief from hardship brought about by ill health or age had only a few options of places to turn. A lucky few would receive ‘outdoor relief’; money for rent, food or medicines from the local Board of Guardians; the unlucky majority would get themselves a ticket to the workhouse. Others may have found charity from their parish church or on occasion, from a particularly benevolent local citizen.

In Lancaster, a fair number of deserving elderly people found aid in the form of the almshouse, of which for its size, Lancaster had several. A place in an almshouse was most coveted; not only was a house provided but a pension and clothing too and there were many more applicants for accommodation than places available. Today, only one of the historic almshouses still exist, though over the years, further ones have been built to take the place of those demolished. Now The Lancaster Charity runs all the existing almshouses, as well as a further one in Morecambe.

- St Mary’s Gate (Vicarage Court/Priory Close) adjoining ‘Greycourt’- Gardyners Chantry is the earliest known almshouse built in 1485 by John Gardyner of Bailrigg. It was rebuilt 1792 but demolished post 1890. It initially had places for four men, later, for four widows.

- King Street- William Penny’s Hospital was set up in 1720 for twelve poor men (later, it allowed two women). A new suit of clothes was provided for each occupant every year. The chapel within the hospital still sees regular use. Two of the cottages were demolished for road widening in 1930 but two more were then built next to the remodelled chapel. This is the only historic almshouse in Lancaster still standing.

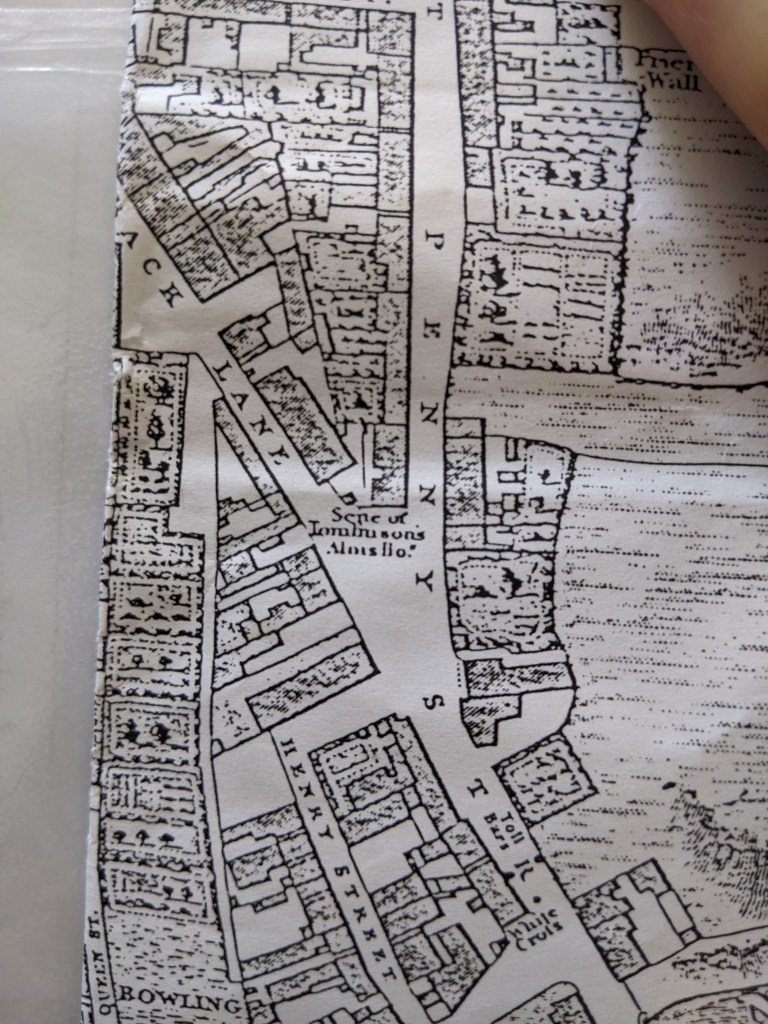

- Penny Street- Townsons Almshouses- It is not known when this early group of 6 cottages by the White Cross were built or even who endowed them but they were demolished around 1812 because it was felt they projected into the road too much. They can be seen on Docton’s map after Kuerden 1684/5, Mackreth’s 1778 and show as ‘site of’ on Binn’s 1821 map, labelled incorrectly as Tomlinsons almshouses.

- Common Garden St- Gillisons Hospital. These almshouses were built in 1790 after the money was provided through the will of Anne Gillison. They housed unmarried elderly women. As well as a pension, each resident received a new gown annually. They were demolished in 1960.

- As well as William Penny’s Hospital, the almshouses that can still be found today are in Queen St; Queen St Bungalows built 1938. Lindow Street & Square- Gillisons Bungalows, 1959 & Lindow Close Bungalows, 1978. In addition there are flats in 16 & 18 Queen St and William Penny’s block of flats on Regent Street, built 1968.

Lancaster’s Stone Benches

Many will no doubt have seen or sat on one of the four carved stone benches, either outside Lancaster Royal Grammar School, Golgotha Village or within Williamson Park. The eagle eyed may have even spotted that one in the park is a bench with a benchmark and the other has ‘Rev T.R. London 1863’ inscribed. There are plenty of myths and legends about these benches, mostly rather gruesome ones (beheading blocks, coffin rests, witches graves, last chance to rest before being hanged). Hopefully, this should solve the mystery of the stone benches.

1863 was the height of the Lancashire Cotton Famine and Lancastrians, due to their dependence on the mills for work, were finding themselves unemployed and facing severe hardship. One of the schemes created to keep the men busy and give them some form of work was the creation of a scenic carriageway on Lancaster Moor. This precursor to Williamson Park became known colloquially as ‘The Top of Hard Times’. The benches, still surviving in and around the park as it became, date to this time. Other towns and cities had similar public schemes at this time, such as Cotton Famine Road on Rochdale’s Rooley Moor.

Looking at the inscription on one of the two park benches, Rev T.R is Reverend Thomas Richardson, born 1830 in Lancaster. Thomas moved to London and eventually became vicar of St Matthew’s Church in the East End. The Reverend became heavily involved in the temperance movement and spent his life working to improve the conditions of those in extreme poverty in the parish he lived in St George-In-The-East. It is believed that Rev Thomas donated money to his hometown to provide some form of relief, he may or may not have also purchased the very similar benches nearby, though they all share a pew-like appearance.

It is believed that the benches were put there, simply as a place to rest oneself after walking up from the town centre and during the labour that these hard-up people were taking to get to either the carriageway where they were sent to work.

Drinking Fountains in Lancaster

On what is supposed to be the hottest day ever recorded in the UK, this seems appropriate. Originally written in 2020 for Lancaster City Museum and edited 2022.

Around the city there are a number of places where the remains of historic drinking fountains can still be found, others we know of only from old photographs. Many seem to have been erected for memorial purposes, often in memory of people who helped advance the health and wellbeing needs of the town. A number, funded by an anonymous donor can be found at the town’s boundaries and stations and would have provided welcome relief to travellers or their horses. I would love to hear of your memories of using the drinking fountains; are there any others you know of?

- Market square. A public fountain with a lantern on top was erected in memory of Dr Edward De Vitre in 1880. De Vitre had been a principal founder of the Royal Albert Asylum and was a pioneer of compassionate patient treatment. He was also mayor of Lancaster twice and head of the Lancaster Gas company who had the fountain made in his honour. Around 1900, the fountain was moved to Queen Square and completely demolished in 1942 to allow for the increasing traffic flow on the main road through the city.

- Rear of the City Museum building New St Square/Market Street corner. This fountain is still partially present, with brown granite and a heraldic dolphin spout, though there’s no bowl now. Provided by the Lancaster Corporation with the funding given by an anonymous donor in 1859 along with three others, it used the newly piped water from the Wyresdale fells.

- Lancaster Castle external walls near to the courts entrance. This public fountain was erected in 1888 in celebration of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee the previous year. The commemorative plaque is still present, along with lion spout, bowl and trough although the water no longer flows.

- Dalton Square. Later moved to Stonewell in 1909, this grand drinking fountain with lantern on top was built in memory of Thomas Johnson, solicitor, and keen supporter of young mens’ health and welfare. It was built in 1895 but the building of the new town hall and further works in Dalton Square required it to be resited. Image of Thomas Johnson- https://redrosecollections.lancashire.gov.uk/view-item?i=232370&WINID=1585769348107#.XoTrgo7YpoM

- Williamson park, in front of the lake. This once grand, canopied drinking fountain was built c.1890 as part of James Williamson (Lord Ashton’s) scheme, continuing his late father’s plans. The canopy was removed in the 1940s and by the 70s a basic municipal public fountain was installed. Today all that remains is the square plinth. Several examples of the original Victorian fountain still survive in Scotland where they were made.

- Wyresdale Rd junction/Lancaster Royal Grammar School wall. This public fountain, sat at the eastern entrance into the town would have been invaluable to locals after walking up the steep hill or travellers entering the town from the moors. Funded by Lancaster Corporation, it was put up in 1859 along with the other group of four. It was originally on the opposite, Lancaster Grammar School side and moved into the Workhouse wall in 1887. It was functioning until the 1970s.

- Lancaster Castle Station, platform 3. Little is known about this fountain; it seems likely to have been installed as one of the group of four in 1859/60 which favoured locations for travellers. The spout plate is embossed with an Indian floral design.

- Penny St/South road/ ashton rd junction. This drinking fountain and horse trough, long demolished c.1930, for road widening works was also placed at the historic southern boundary into Lancaster, close to where the old toll house stood. This too is probably one of the four donated fountains which provided relief to travellers entering the town.

- Yorkshire House, Green Ayre. This one is also gone without trace but was provided in 1860 as a replacement to an earlier fountain and was part of the group of four fountains given to the town by a mysterious donor. It was described as being a handsome bronze fountain and had attached cups ‘in lieu of ladles’. It would have served travellers arriving at Green Ayre Station and from the northern roads. There was a second drinking fountain on the station platform, just like at the Castle Station.

Image courtesy of Lancashire Red Rose collections, Lancashire County Council.

Image by Lancastrian Research.

Image by Lancastrian Research.

Postcard courtesy of Lancaster City Museums.

Image by Lancastrian Research.

Image by Lancastrian Research.

Courtesy of Lancaster City Museums.

Courtesy of Lancaster City Museums.

1845 Town survey map, courtesy of NLS Maps