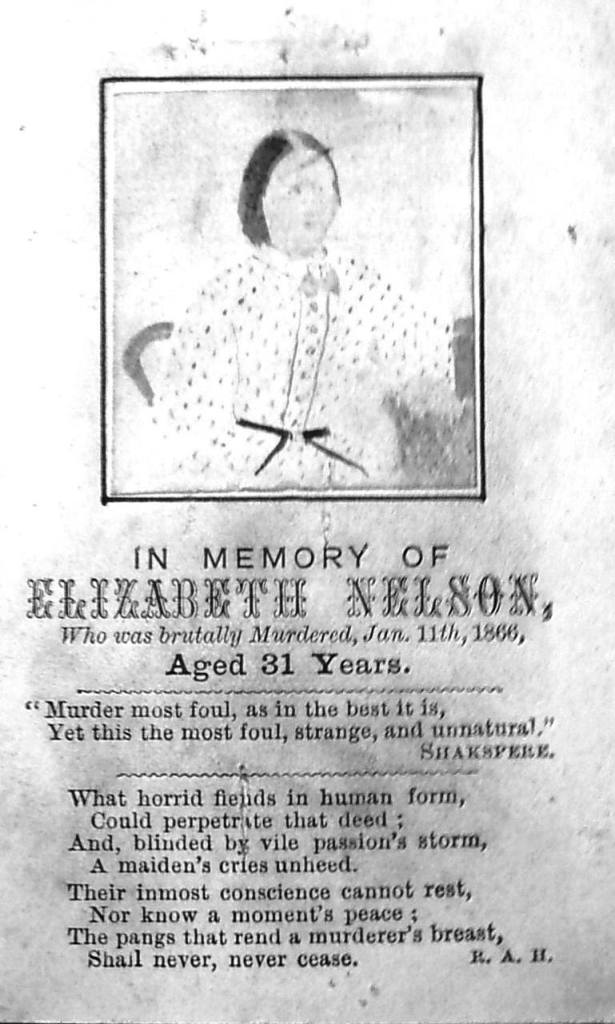

On a winter’s evening in January 1866, 31 year old housemaid Elizabeth Nelson set off from Richmond House on Slyne Road where she worked to deliver a bonnet and a letter. She was never seen alive again. The next morning, on a remote back lane between Bailrigg and Ellel her body was found. She’d been strangled to death with clear signs of both physical and sexual assault. Quite rightly, the inhabitants of Lancaster were greatly disturbed, both at the brutality of the crime and that no-one was ever convicted.

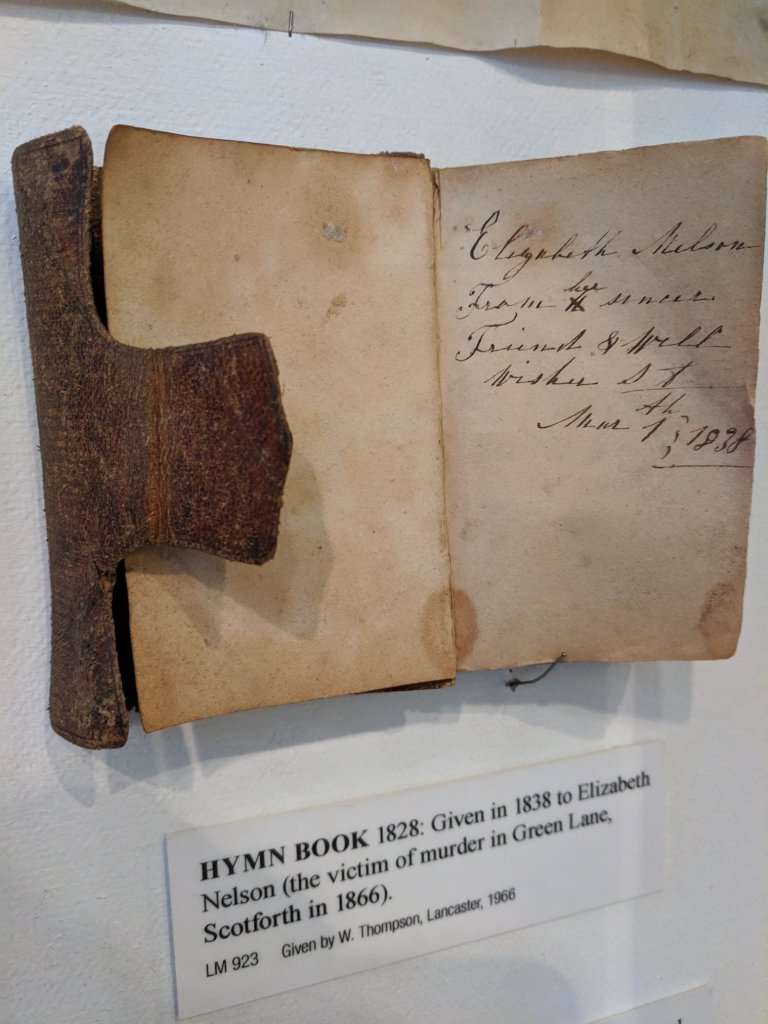

Elizabeth had been born just outside Kirkby Lonsdale, coming to Skerton, Lancaster with her mother Mary at a few months old. Mary began working as a servant/ housemaid at a young age, working for the Jolly family for many years and settled in Skerton with her mother where the Nelson’s made their home.

By January 1866 Elizabeth had been working for the Whalley family of Richmond House for just under a year when she decided to set out in the dark. She had discussed posting a letter in town which had been waiting on the side table all week, when she left the house around 5.30pm. The letter she took contained a bill and was for George Miller who lived at Burrow, between Scotforth and Galgate. It had been incorrectly delivered to Richmond House, instead of to the farm owned by her employer, Mr Whalley at Burrow where Miller worked. Initially, other household staff would comment that it seemed strange that Elizabeth would hand deliver this letter when it could have been taken to Skerton or even Lancaster post offices. Enquiries would later reveal that Elizabeth had been courting George Miller, who worked as a farm labourer at Burrow (now known as Burrow Heights Farm). Delivering the letter personally would have allowed Elizabeth to have met up with her boyfriend. The bonnet which she also took, was firstly delivered to an address in Middle Street in the town centre and belonged to Mrs Rebecca Barrow who was sister to her fellow housemaid Ann Williamson. After a moment’s visit, Elizabeth left. Mrs Barrow, the homeowner, was the last definite witness to see Elizabeth alive.

Elizabeth was heading to Burrow, a distance of two miles south from Lancaster. Despite the darkness, the hour wasn’t especially late and a number of people were walking along Greaves Road and the turnpike that evening, though none could definitively recall seeing Elizabeth when questioned at the inquiry. The only possible sightings were from Mr Welch, of Burrow House who was returning from the Boot & Shoe with his horse and cart around 7pm when his horse whinnied and he was aware of a black clothed figure standing just by the two mile marker stone. The other was from a Master Bleasdale who was standing at the gates to Mr Paley’s property at The Greaves when he thought he saw a woman all in black, with a veiled face and a plaid shawl. This did accurately match the clothes Elizabeth had been wearing that night, the shawl had been borrowed from her fellow housemaid at Richmond House. Her almost colourless outfit could well have been the reason so few people saw her that night.

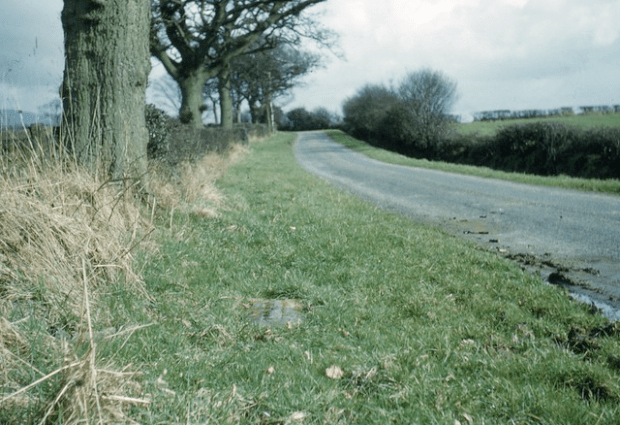

The lane where Elizabeth ended up was over half a mile further on and on the opposite side of the turnpike to Burrow where she had been heading. Elizabeth had only been to Burrow once before, in daylight the previous summer and it was uncertain whether she had lost her way in the dark and either ran up or was led up the track locally known as Green Lane or Barrow Green Lots Lane which connected Chapel Lane to Hazelrigg Lane. Both were quiet rural routes that provided a shortcut between Ellel and Bowland to the turnpike. The only features in this track were small gravel pits. Even in its day, the remote Green Lane was described as overgrown and little used.

Just over a mile away around 7.30pm in Ellel, silk spinner James Beck heard a woman’s screams coming from the direction of where Elizabeth’s body would be found. His dog began barking as the scream abruptly ended. Just over an hour later, snow began to fall.

The next morning around 9am, Elizabeth’s body was found in the snow by farm worker Thomas Wilkinson. Wilkinson raised the alarm with nearby farms and the Galgate police were alerted. Elizabeth’s arms and lower half were covered by snow though it had melted due to her retained body heat on the top half. There was no snow under her, revealing she had died before it had begun to snow about 8.45pm the previous night.

It was over 24 hours after her disappearance when concern for Elizabeth’s whereabouts grew at Richmond House in Skerton that Adam Lund, the stable groom after enquiring at her mother, Mary Nelson’s house at Skerton went to Skerton Police Station to report Elizabeth as missing. Officers revealed to him that the body of a similar aged woman had been found early that morning in Scotforth and Lund went directly to the Boot & Shoe public house where Elizabeth’s body had been taken, positively identifying her before presently returning back to his employers on Slyne Road.

The letter she had meant to deliver to George was found some time later by John Baines of Bigforth Farm, close to where Elizabeth’s body had lain as well as some false teeth which she had worn.

At the coroner’s inquest and then inquiry that followed the key suspects in the case were two local farmer’s sons; John Cottam, aged 24 of Five Ashes Farm and his friend Joseph Dunderdale, aged 20 of Burrow Farm. They were and potentially still are, the most likely culprits that were arrested and questioned though both were later released. They lived on neighbouring farms and could not give accurate or corroborating accounts of where they (Cottam especially) had been between 7pm and 8pm the night of the murder. Dunderdale had made two short visits during this time to see his girlfriend, Jane Procter at Burrow Beck Farm (the discoverer of Elizabeth’s body, Thomas Wilkinson, also lived and worked there). Their discrepancies in accounting for all their time out of their homes that night did give time (for Cottam) to have committed the murder, though when he came to visit nearby Burrow House at just after 8pm, he appeared neither dishevelled nor changed from his usual character in the opinions of the farm workers he spoke with. They did however say it wasn’t usual for him to turn up there and speak with them. During his later examination, some unexplained blood stains were found on a handkerchief and in the seat lining of his trousers though experts could not say with any confidence whether these were human or animal or likely to have been caused by the scurvy from which Cottam suffered. When repeatedly questioned, Cottam claimed not to know Elizabeth Nelson personally, though details later emerged through Elizabeth’s friend Ellen Cleminson that John Cottam had met Elizabeth before and they had all attended a local town dance at the Cross Keys together. Elizabeth had declined to dance with John but did stay at the dance with him after Ellen left. It also emerged later that Elizabeth turned Cottam down after he tried unsuccessfully to court her, saying she much preferred George Miller. Dunderdale confirmed he had previously met her at Richmond House. In addition, as landowners for the Scotforth parish- both Cottam and Dunderdale’s fathers sat on the inquest jury that was held at Scotforth Primary School. After his arrest, Dunderdale was bailed by his own father. Elizabeth’s boyfriend, George Miller was never a real suspect in the case as he remained at Burrow all evening as testified by the Gornalls who he lived there with. Cottam was held on remand at Lancaster Castle for over three weeks and was brought to the Town Hall inquiry four times before the magistrates finally agreed there was insufficient evidence against him to proceed to a criminal trial.

For a time even the police sergeant, John Harrison who was summoned to the crime scene was implicated; he made the damning mistake of requesting Elizabeth’s body be taken away and washed by three local woman at the Boot & Shoe, before any medical professionals or other judicial officers could examine it, potentially washing away any evidence. By the time Sergeant Harrison had been to inform the coroner, his Superintendent and Dr Hall, a surgeon who would perform the post-mortem later that evening, it was 2.30 in the afternoon and the body had been stripped of all clothing and all bodily fluids washed away. This was a huge mistake for a policeman of over 20 years and it was many months before he was finally vindicated though no doubt demoted for his negligent decision that morning.

At the inquest, it was revealed what had happened to Elizabeth that night. Elizabeth’s underskirts were soaked in blood and the two women who had cleaned her body described how she had had blood down her thighs coming from her genitals. More visibly, she had large bruises over both eyes and the top of her head with blood from her temples, nose and mouth as well as others on her arms, thighs and groin. A handkerchief had been double knotted around her neck, though not to the degree that it alone could have strangled her. The coroner noted that she had been penetrated by a blunt object which had perforated her posterior vaginal wall. Her thyroid cartilage had been crushed, suggesting that she had been strangled with pressure from the thumbs and potentially from a left hand. That and the blows to the head had caused her death. The bruises on her arms and dirt on the backs of her gloves show that she had had her arms pinned down to the ground. All this suggested to a number of the experts that a second person could have been involved in the murder.

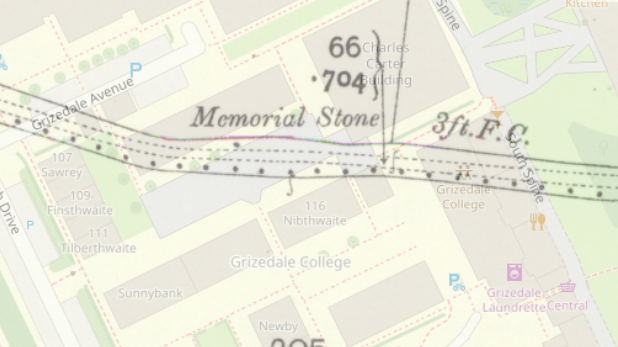

After the murder, by public subsciption, a benefit fund was raised for Elizabeth’s mother Mary and a memorial stone was made for Elizabeth (the stonemason initially refused to accept payment for it) and in late March of that year it was placed on the spot where Elizabeth’s body was found on Green Lane. Mawkish visitors quickly stripped the surrounding trees and bushes of twigs and branches as souvenirs. The lane itself became devoid of greenery due to the literal sea of human traffic to the site, though a spade mark was made where Elizabeth’s head had rested and this spot remained untrodden. This site of the memorial plaque was marked on OS maps of the time and could still be visited until the 1960s when Lancaster University began developing the land all around Bailrigg and Hazelrigg. Today the memorial site is no longer a quiet bylane but is the heart of the campus of the University. Grizedale College and the area immediately fronting Grizedale bar is today the location of the memorial stone where it can still be seen on the side of a large stone planter. The chapel lane, as it was then called, leading off the A6 up past Lancaster House Hotel and into the University campus is now called Green Lane in its entirety. Behind Grizedale College, a final section of the original tree-lined Green Lane remains alongside the George Fox Building. It is eerily incongruous amongst all the other contemporary university buildings.

Elizabeth was buried at St Saviours, Aughton near Halton on 15th January 1866. Her mother Mary is buried with her.

Despite rewards for information leading to the capture of the culprit/s no one was ever found guilty of the crimes. It later emerged that another attempted rape and assault of a servant girl had taken place on the chapel lane on October 20th the year before. The description of the attacker was of a small man in dark clothes with a brimmed hat. He had grabbed her round the neck. This was not the first such attack; Margaret Townson of Scotforth Mill was attacked whilst heavily pregnant whilst going out early morning in July 1860 to see to the cows. Her attacker was a well known scoundrel, William Green or ‘Cocker Green’ (aged 23) who had held her by the throat while attempting to rape her. He was a well known poacher who knew all the fields and rural areas around Scotforth, Ashton and Wyresdale well. After the attack he was imprisoned for two years at Preston.

Postscript Notes-

John Cottam was killed in his job as a horse breaker in 1889, aged around 47.

George Miller married a previous girlfriend in Garstang five months after Elizabeth’s death.

The ‘boggart’ house which is mentioned frequently throughout the case refers to Oubeck House (now Oubeck and Chadderton Cottages) on the opposite of the turnpike (A6) to the junction of Chapel Lane (now Green Lane).

An interesting feature of the case highlights the inconsistencies in how time was measured locally. A detailed minute by minute account of all the key witnesses as well as the timeframe of Elizabeth’s last journey was undertaken and what becomes clear is that almost all recipients had their clocks set to different times, particularly in the more rural Burrow and Ellel localities. The mill at Ellel, the farms at Burrow, ‘town time’ and ‘railway time’ all refer to a different way of measuring the time. This is despite the railways introducing a standardised way of measuring the time almost 25 years prior. This no doubt involved a huge additional headache to those trying to to work out the timeline of events in the case.

Sources

Lancaster Guardian, Lancaster Gazette, Preston Chronicle